This article contains information about residential “school.” Please read with care and reach out if you need support. The Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line can be reached any time at 1-866-925-4419.

Good on the government of Canada for declaring Sept. 30 a national holiday to recognize truth and reconciliation.

I want to first speak about a traumatizing truth still in need of reconciliation and resolution. I was traumatized while a student at the Alberni Indian Residential “School” for nine years.

I wrote a 10-page foreword in Celia Haig-Brown’s book, Resistance and Renewal: Surviving the Indian Residential School. That book I published in 1989 was about the Kamloops Indian Residential “School.”

Around that time the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was released. It spoke about sexual abuse and missing children in Indian residential schools across Canada. Phil Fontaine, the former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, in 1990 announced publicly he had been sexually abused in a residential “school.”

I was traumatized again in court. I was a plaintiff in the precedent-setting B.C. Supreme Court case, Blackwater et al., that led to thousands of residential school survivors being compensated.

I was in court for five years or more. It began with the criminal trials of Arthur Henry Plint, a former dormitory supervisor at the Alberni school. He was sentenced twice to 11 years in prison.

Then it went into determining who else was liable. This portion began in Nanaimo and the lawyers’ final arguments were heard in Prince Rupert.

The support there was amazing. The community centre was jam-packed full of people with feasts, dancing, singing and people standing up to share their Indian residential “school” stories for the first time ever.

We went to visit a couple of reserves and churches to share our stories about why we were there.

The judge declared that both the Government of Canada and the United Church of Canada were liable for abuses suffered by children under their care.

The actual civil case and settlement conferences took place in Vancouver and Richmond.

The settlement conference was traumatic because the settlement offered to me was ridiculous. So, I went on in court rather than settling for a pittance out of court.

I still ended up with a pittance. It was traumatic again when the lawyer took nearly half of my pitiful settlement. The plaintiffs in the Blackwater case were trailblazers. Our case was responsible partly for the trail leading to today’s reconciliation.

Yet, we were the only ones who had to pay legal fees. That is so unfair. This would be a simple step for reconciliation to repay the Blackwater plaintiffs their legal fees.

Enough about trauma. Let’s look at reconciliation.

I suffer with post-traumatic stress disorder from nine years in the Alberni Indian Residential School.

So, I went through that and then went through that horrible court case. I have had many opportunities to speak with people about the meaning of reconciliation.

My take on it is that reconciliation is a two-way street. Sure, it’s vital that everyone learn about First Nations. At the same time, I believe it’s important for First Nations to learn about others.

I’m Tseshaht and our home is in Port Alberni and Barkley Sound on the West Coast of Vancouver Island.

Even though my people are on the other side of the mountain, our language and culture are different from the Salish. Before I started school in Port Alberni, I spent my childhood in paradise in the Broken Island group.

I acknowledge I am now in the traditional territory of the Snuneymuxw people. Therefore, I am a guest here just like anyone else.

My desire to bring people together culminated in One in Spirit Walks being launched on Sept. 30. The walks will be limited to 10 participants. Dr. Ansel Updegrove will accompany us to ensure the physical and emotional safety of the walkers.

I will open with a traditional song, then briefly speak about the history of Westwood Lake, then I will share my story. We will walk and stop when someone else is ready to share their story. When we reach our destination we will share a lunch.

These walks are based on the fact that stories can be healing.

When we know the level of interest we will organize some walks for October at other locations in this region then more in the spring. We are hoping people of all races and ages participate.

This is one way people can help move reconciliation forward. Reconciliation is about love, peace, and happiness! Hey, where did I hear those words before? [end]

Recommended reading:

Resistance and Renewal: Surviving the Indian Residential School by Celia Haig-Brown

Stoney Creek Woman: The Story of Mary John by Bridget Moran

Indian Horse by Richard Wagamese

Five Little Indians by Michelle Good

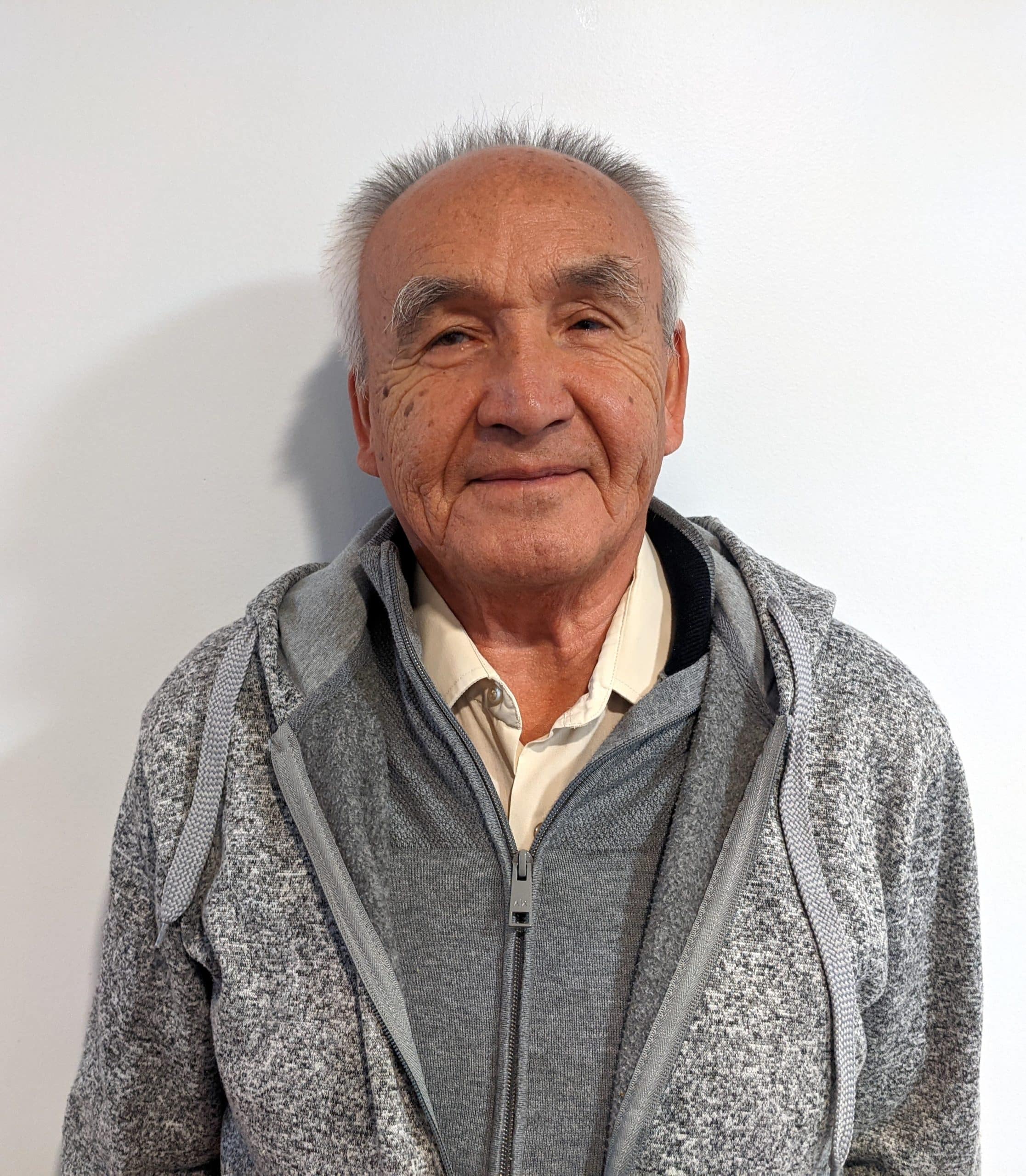

Randy Fred is a Nuu-Chah-Nulth Elder and writer. He has spent his life working in different media, from radio to books to magazines. He is the founder of Theytus Books, the first Indigenous-owned and operated book publishing house in Canada. He lives in Nanaimo, Snuneymuxw territory.