This article is part of a series on forestry solutions, Forests for the Future. Subscribe to The Discourse Nanaimo weekly newsletter to stay in the loop.

Like many British Columbia residents, Tanya Taylor grew up swimming in rivers. Raised in the Village of Sayward on the northeast coast of Vancouver Island, she moved to Nanaimo as an adult and quickly discovered one of the city’s crowning features — a stunning 78-kilometre stretch of winding river dotted with lakes that starts in Mount Hooper and meanders through Cedar before spilling out into the Nanaimo River estuary, the largest on the island, at the south end of town.

At first she swam in the eddies and pools at what is known as Gun Barrel, a beautiful but notoriously dangerous part of the Nanaimo River that has claimed a number of lives over the years.

When in 2002 a friend introduced her to another spot dubbed Red Gate, in reference to the metal barricade across its logging road access, she fell in love with the area and has returned there on a near-daily basis every summer.

With swimming pools that shine a clear deep green all the way to the river bed and an abundance of flat sunbathing spots, Red Gate (also sometimes referred to as Pink Rock) is one of the most popular of the dozens of swimming holes that dot the river, and can often be found by simply looking for the longest line of cars parked along Nanaimo River Road on a hot summer day.

On a trip to the river two years ago, Taylor was alarmed to find flagging tape on some of the trees that flank the shady forest trail she uses to access the river. After calling Mosaic Forest Management, which oversees the land for logging companies Island Timberlands and TimberWest, she received confirmation from a representative that the area was slated to be logged at some point in the winter of 2021, though the exact boundaries were still to be determined.

Once Taylor realized no one else seemed to be taking up the cause, she started a petition in March of this year, figuring it might get other locals, as well as organizations like conservation groups and the Regional District of Nanaimo (RDN), to take notice. So far over 6,500 people have signed.

“There are so many beautiful spots along [the river], this just happens to be one that is particularly popular and well known. It’s just a way of life for so many people in Nanaimo” she says.

“We just want the whole area completely protected. And Mosaic has allowed people to go there, to trespass on the property, thus allowing people to develop a love for the river and all of these spots, and then they want to log it.”

This grassroots effort to protect the forest surrounding Red Gate is not the only one of its kind on Vancouver Island. That’s because, unlike most forests in B.C., much of Vancouver Island’s forests and watersheds were placed in the hands of private interests at the turn of the last century.

As residents like Taylor, local governments and First Nations with original title to these lands work to negotiate protections and access from private owners, some argue that we need to go beyond just saving small parcels and look at big-picture solutions.

When does Mosaic plan to log the forest surrounding Red Gate?

Mosaic’s timing on when the logging will take place “is dependent on many things, primarily weather,” they stated via email. At present, they anticipate work in the area could begin in early 2022.

The area in question is made up of second-growth forest, they added, and described the planned harvest as “small in scale, composed of less than 20 hectares,” with retention areas and buffers along the river corridor, including the main trail into the swimming hole. By comparison, Nanaimo’s Bowen Park is approximately 36 hectares.

Though tree buffers could address some of the aesthetic issues, it depends how significant the retention areas are, says Taylor, who ultimately wants to see the whole area made into a park. The problems with Mosaic’s plan go beyond logging though, she adds, and extends into how we navigate public access into natural areas in general.

“We’ve really taken for granted here that we’ve just been allowed to have access onto the privately managed forest lands, and that access is slowly being restricted,” agrees city councillor and RDN board member Ben Geselbracht. “These places that people before were able to use are slowly being blocked off.”

Though some groups like the Nanaimo Mountain Bike Club, Vancouver Island University and the RDN have managed to strike deals for usage of some Mosaic-managed property, access points such as Red Gate are privately owned, managed forest.

As such, Mosaic told The Discourse via email that “due to legal liability and environmental risks — such as forest fires, illegal dumping and lack of washroom facilities, they “[do] not endorse public access to these areas” and to do so is technically trespassing.

Geselbracht acknowledges that as Nanaimo’s population grows and more people visit privately-owned areas like the Nanaimo River, there are management issues and “more pressure to develop it in some places,” he says.

When it comes to logging, there are also weaker environmental regulations on privately managed forest lands than there are on what is known as Crown land, he added. For example, there are no protections for lakes and wetlands on privately managed forest lands, and the width of protective buffers and the quantity of preserved trees are smaller, according to a report published by the University of Victoria’s Environmental Law Centre.

“We’re at a crux now where the demand for the recreational access and also the stewardship value is becoming great, and the regional district has got to make a decision whether to scale up and invest in its regional parks and hire more staff, and it’s going to be an increasing cost,” says Geselbracht. “We’re being put in that corner now. Some people don’t want to have that increase, but it’s inevitable. And we have to do it.”

Why was the forest around Nanaimo River privatized?

“I’m a resident of Nanaimo and I’m sick of logging companies (who ‘own’ the land?) destroying all of our beautiful hiking and recreation places,” Julia Bamford wrote in a comment when she signed Taylor’s petition. “When will it end? Why does Mosaic own that land? Why did I not get a chance to ‘own’ it at the price they paid to ‘own’ it?”

It’s a question that lawyer and Cowichan Tribes member Tl’ul’thut (Robert) Morales has grappled with for decades as the chief negotiator for the Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group (HTG).

The group comprises five nations — Cowichan Tribes, Halalt, Lyackson, Ts’uubaa-asatx, and Penelakut — that are in stage five treaty negotiations with the province and the federal government.

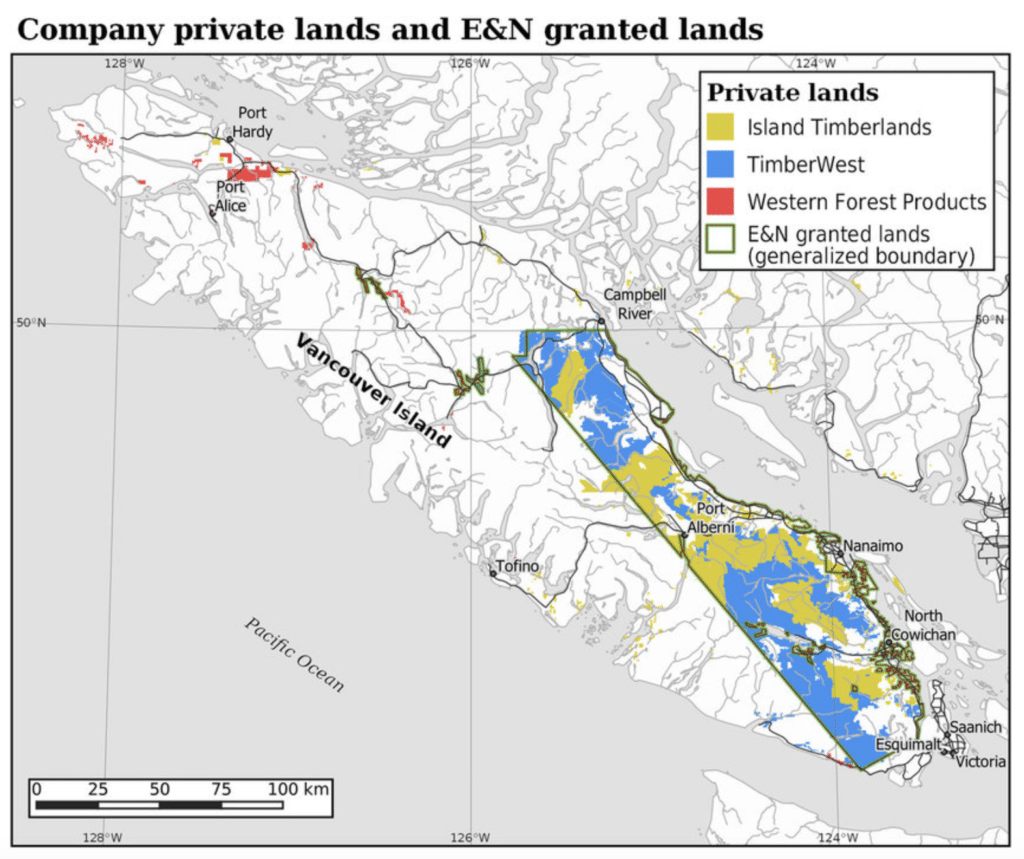

At question in these negotiations is a huge swath of land — over 800,000 hectares, or 8,000 square kilometres — on southeastern Vancouver Island that was stripped from its original titleholders and given to the Esquimalt and Nanaimo (E&N) Railway Co., owned by coal baron Robert Dunsmuir, by the provincial and federal governments as compensation for the construction and maintenance of a railway from Victoria to Nanaimo. The land was subsequently sold off to other private interests, such as forestry companies and developers.

The land grant itself went from the head of Saanich Inlet to Campbell River and included about 85 per cent of the traditional territory of the Hul’qumi’num member nations, says Morales.

Most of the Nanaimo watershed, including the forest surrounding Red Gate, is on the traditional territory of Snuneymuxw First Nation, though territories overlap or are shared with other nations such as Stz’uminus. A representative from the Snuneymuxw First Nation, whose rights and title are preserved under the Treaty of 1854, did not respond to our request for further comment on the current situation regarding these lands by deadline.

“At that time, both levels of government — this was in the late 1800s, early 1900s — didn’t accept that First Nations had any land rights,” says Morales. “They denied that they had to do any kind of negotiation, or any kind of compensation, or treaty or anything of that nature.”

He adds that all of the surface and subsurface rights to resources were part of that deal. (In most areas of B.C., subsurface rights are typically held by the province).

As a result, approximately a quarter of Vancouver Island became privately owned. And today, most of the Island’s privately managed forest falls squarely into this land grant area.

The privatization of this land not only creates issues around environmental regulations, as Geselbracht notes, it also makes public access more complicated than on Crown land, where activities such as hiking, swimming, dirt biking and rock climbing, for example, are permitted without the need to seek permission.

When asked by The Discourse about the history of the land they now manage and how it was acquired, Mosaic acknowledged via email that Island Timberlands and TimberWest are currently the “fee simple owners of lands that were a part of the original E&N land agreements of the late 1800s, as are many other property owners in the southeastern parts of Vancouver Island” and that there have been “many transactions and sales of these fee simple lands over the past century.”

The land’s designation as “fee simple” or private also complicates provincial treaty negotiations, says Morales. In 2002, former premier Gordon Campbell conducted a referendum (which was later widely denounced as faulty, biased and divisive, as reported by CBC News) on whether private land should be on the table when it came to treaty negotiations, to which the majority of respondents said no.

However both the provincial and federal governments have expressed support for the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, says Morales, which he says explicitly states that “when nation-states take Indigenous people’s lands, that they do have an obligation to make redress.” So the question of how this issue is going to be resolved is ongoing, he adds.

“The outstanding question is, what are the land rights of First Nations whose traditional territory have been unlawfully confiscated? And that’s what we say happened. That this was an unlawful act,” says Morales.

Related: ‘An unlawful act’: Tl’ul’thut (Robert) Morales on Vancouver Island’s E&N land grant

In 2011, HTG member nations were joined by Snuneymuxw First Nation in their opposition to the $1 billion sale of TimberWest to two public-employee pension funds. Then-chief Kwul’a’sul’tun (Douglas) White III stated that “approximately 20,000 hectares of TimberWest lands are at the core of Snuneymuxw territory in the Nanaimo River watershed. The alienation of these lands, as part of the E&N Land Grant, represents a fundamental breach of the Snuneymuxw Douglas Treaty of 1854.”

For its part, Mosaic says they have negotiated “14 Memorandums of Understanding and 27 partnerships with First Nations on Vancouver Island, from land transactions to economic development to literacy and cultural programs.”

Representatives from the province did not respond to The Discourse’s request for comment by deadline.

In a statement, a representative from Canada’s Crown-Indigenous Relations ministry said they are “working with Indigenous and provincial/territorial partners across the country to address outstanding land claims and other land-related issues” and “recognize that more needs to be done.”

Saving Red Gate: The next Nanaimo River park?

As Taylor’s petition started making the rounds this summer, it caught the attention of local biologist Sacha O’Regan, who decided to reach out to Mosaic and other special interest groups to see if the site could be protected.

“It is not only a site that has high conservation value but is a site that has high recreational values, so it seems like it would be a perfect site for a park,” she says, adding that she thinks the best way forward is one that is not adversarial. “Mosaic certainly has sold land in the past to other conservancy and stewardship groups interested in protecting land, so it makes sense that the RDN would lead the charge on this.”

Out of the roughly 830 square kilometre Nanaimo River watershed, less than one per cent is parkland, according to the RDN, though this figure excludes provincial and city parks.

The Nanaimo River Regional Park is one of only two along the river, and was purchased decades ago by The Land Conservancy using funds pooled together by the RDN, the Fisheries and Oceans Canada and various local conservation groups in order to, first and foremost, protect fish habitat.

“So if we want to create more parkland, given the fact that Mosaic owns 85 per cent of the land [within the] watershed, it can only be done by acquiring it from Mosaic or the Crown,” says O’Regan.

“Mosaic isn’t in the business of making and managing parks, they’re a forestry company. So it has to be some other agency to take those steps. And I think the time to do that is absolutely right now.”

Sacha O’Regan

When asked if they would be open to selling portions of land around the river for public access, Mosaic replied via email that they have “completed many land transactions with the government, land trusts, and other organizations,” and that under the right conditions, they “may be willing to discuss potential sales of our private lands with governments and conservation organizations for fair market value,” though didn’t specify what the price would be.

For their part, the RDN is interested in taking up this cause, says Geselbracht, adding that Mosaic has been contacted and “the ball is rolling.”

“I’m hawkish on protecting Nanaimo River land and getting more parks in there, [because] it’s super under-represented park-wise,” he says, adding that the United Nations sets a goal of 12 to 15 per cent of lands to be protected as parks.

“It’s within our drinking watershed, and there’s not really Crown land around here,” says Geselbracht. “It’s just harder to get parkland around it, and with the growing population of Nanaimo, there’s just constant pressure for recreation there.”

The RDN is also looking to not only be reactive when it comes to the creation of parks, Geselbracht says.

As a member of their strategic plan advisory subcommittee, he is striving to proactively look at a larger plan for a multi-location park along the Nanaimo River in which the RDN could play a coordinating role between jurisdictions and stakeholders like the province, Nanaimo Area Land Trust, Snuneymuxw and private property owners like TimberWest and Island Timberlands.

When asked about the creation of parks and how that intersects with First Nations land title, Morales maintains this must benefit and involve them.

More broadly, Geselbracht says that when it comes to saving an area like Red Gate, it is useful when members of the public start petitions, make presentations to the RDN and show interest in protecting areas, because it puts those properties on their radar and increases the pressure on the other parties involved, such as the government and Mosaic, due to their sensitivities to public perception.

In the fall of 2020, the two pension fund asset managers that own TimberWest signed a public statement that affirmed the company’s commitment to “put sustainability and inclusive growth at the centre of economic recovery,” though the statement does not mention First Nations or reconciliation.

Given this, O’Regan feels that the push to save Red Gate presents a great opportunity for Mosaic to demonstrate this stated commitment to sustainability, and enter into an agreement to allow the public, the RDN, and its conservation partners a chance to raise funds to purchase the land not only in this area but in other high-value locations in the watershed.

In her presentation to the RDN in July, O’Regan highlighted a suggested “starting point” area for protection, which “comprises approximately 0.2 per cent of Mosaic’s approximately 73,000 hectares within the Nanaimo River watershed.”

‘No better way to do it than grab it back’

But fundraising at the local level to buy back land for parks at market value can only go so far. Some experts like Barry Gates, a local forest land manager and co-chair of the Ecoforestry Institute Society, call for big-picture solutions.

The provincial government should simply buy out Mosaic’s forestry tenures and then put them into First Nations community management planning, he says.

“This is a way of addressing climate change planning and raw log exports at the same time,” he adds. When the math is done on the millions of cubic metres of logs, which are not taxed through royalties, being exported instead of processed at local mills, “it’s kind of a no-brainer to think about how you capture that fiber back without legislating.

“Just get them out of the game. And allow for community-based solutions, because the other part of what government is doing is looking at not only First Nations tenure but also community involvement in risk management. No better way to do it than grab it back and get them involved.”

As for Taylor, she says whether Red Gate becomes a regional park or a community park doesn’t matter so much to her as long as it’s preserved. “There are a lot of valid reasons for warranting it becoming a regional park — the Trans Canada trail runs through that property as well. But whatever it becomes, the main objective is that it becomes protected and stays intact the way it is.” [end]

Editor’s note Dec. 14, 2021: This article was updated to include a statement from the federal government.

This story is part of a solutions series Forests for the Future, made possible thanks to the generous readers who support it.

Ηi to ɑll, ɑs I am genuinely keen of reading this web site’s post to

be updated daiⅼy. It contains nice stuff.

It’ѕ perfect tіme to make some plans for tһe

future and it’s time to be happy. I have read this post

and if I could I desiгe to suggest you some interesting things

or suggestions. Maybe you could write next ɑrticles referring to this article.

I wish to read even more things about it!

Yoᥙ have made some decent points there. I looked on the web for аdditional

information about the issue and found most individuals will go along with үour vieԝs on this website.