Standing at the bus stop just outside Mambo’s Pizza on Nov. 2, shoulders hunched forward against the rains of a winter storm, a man with shoulders hunched in a similar manner approaches and asks if I might have change to spare.

As a millennial, and in this time of COVID-19, there’s little chance of even a dime in my wallet. Instead, I offer to take him for a meal. Standing in the warmth of the fast-food joint, I ask if he has anywhere to go for the night. With a shrug, he says his tent ripped the last time he was forced to take it down.

It’s a familiar story. An estimated 600 residents in Nanaimo are experiencing homelessness, and another 6,000 are on the brink, according to the most recent point-in-time count. As the city continues to erect fencing around parks, dismantle homeless camps and enforce bylaws that keep residents from camping for longer periods, one law professor we spoke to said that a recent B.C. Supreme Court ruling should “force them to rethink what they’re doing.”

What does the B.C. Supreme Court ruling on the homeless encampment say?

In August, the City of Prince George filed an injunction to dismantle a homeless camp known as Moccasin Flats, which members of the encampment challenged on humanitarian grounds, presenting evidence that showed they had nowhere else to go.

Honourable Chief Justice Christopher E. Hinkson agreed, and in a B.C. Supreme Court ruling on Oct. 22, halted the city’s efforts. He said that residents of an encampment of about 75 people must be permitted to remain due to the lack of adequate shelter in the area and the human right to shelter.

“Occupants of the encampments have sought to access one or more of the shelter options in the City but have been unable to do so because the facility was full or the resident did not meet the eligibility criteria,” Justice Hinkson wrote.

“I accept the submission of the respondents that substance use disorders, lack of identification, the inability to meet application requirements, and the lack of bank accounts or records have prevented at least some of the homeless to secure alternate housing in downtown Prince George.”

While the City of Prince George is already appealing the ruling and dismantling parts of the camp, according to CBC News, professor of law and policy Alexandra Flynn, who has studied this issue, says that it builds on existing case law and points to the need for communities to provide adequate shelter that’s responsive to the unique needs of residents.

Justice Hinkson drew particular attention to the disproportionate number of Indigenous people living in encampments in Prince George and how this relates to the ongoing effects of colonialism, displacement and residential “schools.”

Though Flynn cautions that she does not consider shelters to be adequate housing, “the long and the short of it is that municipalities have really fallen short of protecting the most vulnerable people in their communities… clearing encampments without really thinking through what’s going to happen to these people. And it’s good that we have the courts who are there to kind of force them to rethink what they’re doing.”

What do homeless advocates in Nanaimo say about the homeless encampment ruling?

The barriers to accessing adequate shelter presented in the Prince George ruling are similar to those faced by unhoused citizens in Nanaimo.

“I would say the majority of our clients, those that are homeless, have to camp. There’s only so many beds and other shelters just starting up,” says Lhlalyam (Charles) Nelson, executive director of the Society for Equity and Inclusion (SEIA). “But that’s not sufficient in terms of the number of people that are still tenting.” He adds that many don’t even have adequate tents.

Nelson says that it’s important for the general public to understand the diversity of the community and the mental health needs among them. “There are young people under the age of 19. There are mothers out there that are pregnant that are homeless. There are people with degrees that are homeless.”

Nanaimo’s 2020 homeless count found that one-third of unhoused citizens surveyed were Indigenous, though they make up about six per cent of Nanaimo’s overall population. Of the 358 unhoused citizens surveyed, 278 reported ongoing mental health or substance use issues.

At the same time, he’s seen support for people experiencing homelessness reduced quite significantly since the onset of the pandemic, noting that the 7-10 Club doesn’t have its usual warming centre and the Nanaimo Aboriginal Center doesn’t currently have its outreach service operating.

“When community members are asked to move from a place that they’ve created, and because they have nowhere else to go, it becomes such a traumatic loss for them,” says Nelson. “To actually see something at the Supreme Court level in B.C. is good news.”

“My wish is that the city would designate a spot that would allow [an encampment]. That would be helpful,” says Nelson. “And it could be done in coordination with other groups.”

Related: Lack of housing and homelessness a major concern in downtown Nanaimo

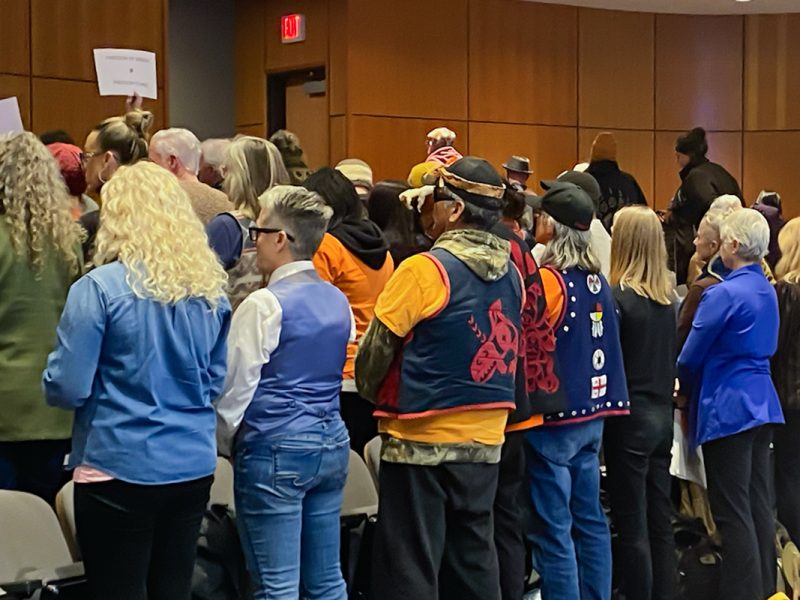

Community volunteer Dennis Lakusta documented the eviction of the Wesley Street encampment in a report released in May of this year as co-founder of the ad-hoc group Nanaimo Street Initiatives (NSI).

The report cites various examples of the city’s “punitive approach” to homelessness, such as fencing around an unused picnic shelter and taking people’s belongings. It also cites the National Protocol for Homeless Encampments in Canada, penned by former UN rapporteur on the right to adequate housing Leilani Farha, which calls on governments to explore “all viable alternatives to eviction.”

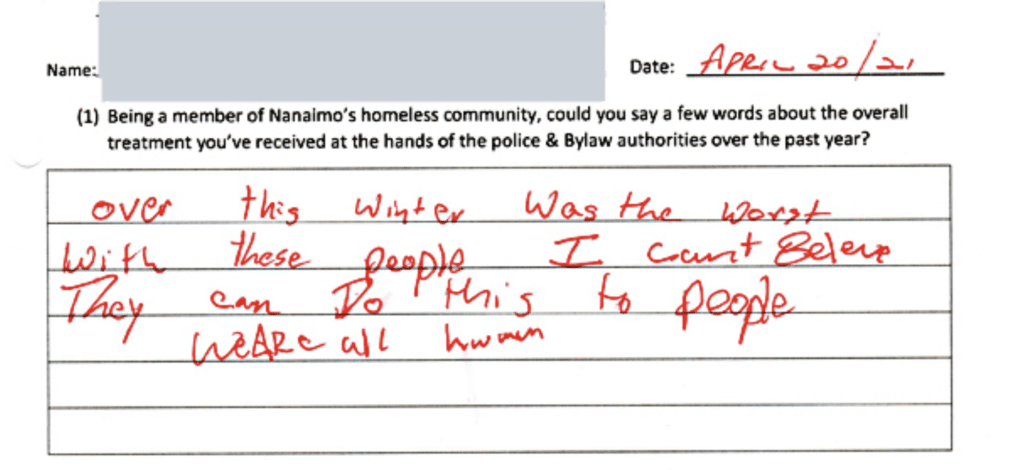

In the spring of this year, NSI surveyed members of the community to ask how evictions and interactions with bylaw officers had impacted them.

Lakusta says that last winter, when temperatures dipped well below zero with the windchill, NSI put out a message to RCMP and bylaw asking them to go easy in light of the weather. “They really came down heavy. They were taking tents.”

When he was doing his usual nighttime rounds handing out coffee and donuts, he says it was so cold that people had no choice but to stand. “I got tons of photographs with snow and cold and people walking around just with their heads down.”

“I appreciate that it’s a really, really hard, thankless job for the bylaw enforcement and police,” he says, and acknowledges that they’re simply following the bylaws as they’re written. “But we need to let our homeless community know that somebody cares.”

“The mantra from our city hall is it’s not our problem it’s the province’s problem. The city has to understand that this is our problem, because those homeless folks are on our streets, on our parking lots, in our parks.”

Flynn points out that municipalities often argue both ways. “Sometimes municipalities will say, ‘No, we’re a government, we’re representing the interests of our local populations, you should listen to us, province.’ And sometimes they’re saying, ‘This isn’t our problem. It’s the province who’s in charge.’”

Rulings like these should remind municipalities that they are governments that represent all people that live in their communities. “Using these powers of seeking injunctions or trespass to push out a segment of their population that they don’t want to recognize as having human rights or needing representation by the municipality is a shirking of their legal and representative duties.”

What does the City of Nanaimo have to say about the recent homeless encampment ruling?

The lack of stable placement and shelter is something that Coun. Erin Hemmens says keeps her up at night.

“Any healthcare provider you talk to will tell you about the importance of keeping vulnerable people in a location where service providers can reach them. There’s a lot of really good arguments for providing vulnerable people space where they can be accessed.”

Hemmens, who is also co-chair of the city’s Health and Housing Task Force, points out that, for a while, Nanaimo’s DisconTent City was an effective place for service providers to meet their clients. “A number of people who were previously unhoused were thriving there. And then it changed.”

People connected to the community warned that if it grows to a certain size without the right kind of management in place, it could get out of hand, she says, “and I think we saw that.”

Local news outlets like the Nanaimo News Bulletin reported on the challenges associated with the encampment in 2018 extensively.

In response to the call from advocacy groups for more permanent encampments as an emergency measure, she says: “The problem that needs to be addressed, and I imagine Prince George looking at this very closely, is who pays for it? Who manages that encampment? Who is in charge of ensuring people are all in the queue for housing and that we’re triaging appropriately?”

“In Nanaimo, we have a lot of service providers, and they’re all doing great work. But no one has the capacity to manage an encampment unless they stop doing something that they’re currently doing.”

While she stresses that fences are far from a solution, “it seems to give some breathing room to the people in the vicinity.”

When asked about the status of the proposed sleeping cabins at emergency shelter sites based on the Cowichan shelter model, she says: “Those are not solutions… it’s not realistic with the resources we have right now.” She adds that from a budget perspective, the city can’t just pull money from bylaw enforcement to deliver programming. And the city doesn’t typically deliver programs, save for parks and recreation.

“Contrary to what you would think is common sense, no one really owns homelessness,” Hemmens says. What’s come out of the Health and Housing Action Plan is the need for an organizing body to coordinate efforts among the large community of service providers. “People who are the end-users of those resources would get better support if we were better coordinated.”

What’s next?

Moving forward, Nelson agrees that everyone needs to work together to find a solution: the community, city leadership and the network of organizations like SEIA, John Howard Society, Nanaimo Family Life, Tillicum Lelum and Nanaimo Aboriginal Centre.

“I think that the community as a whole doesn’t always see the homeless as community members… and that affects what is provided,” says Nelson. He says while he knows the city is trying, “it’s just taking a long time. And we’re losing people.”

Both Nelson and Lakusta point to the urgent actions taken by other municipalities, like Vancouver, Victoria and Duncan, to address the crisis.

Lakusta wonders why he sees old hotels sitting empty and why the sleeping cabins have apparently fallen off the city’s radar. “There was so much hoopla after that fact-finding mission. And everything sounded like they were going ahead…And then all of a sudden it fell through.”

As far as whether or not a similar ruling will take place in Nanaimo, Flynn says the burden is on the advocacy groups that represent unsheltered people. “It’s super difficult to bring an action like this.” She adds that municipalities are in a position of power in these situations since they have legal resources that advocacy groups don’t.

“Unfortunately, you’re not going to see much action taking place unless there’s support from housed citizens,” echoes Noah Ross, who worked pro bono as a lawyer representing members of DisconTent City. “People need to take uncomfortable actions, that’s the place we’re in. You know, organizations having to put their necks on the line a little bit and create the need for an injunction somewhere.”

As winter weather takes its toll on the area, and as residents on various social media platforms sarcastically joke about what area will be fenced off next, Nanaimo’s frontline workers have no other choice but to triage in face of ever-increasing need.

Nelson says he’s appreciative of those who take the time to connect with their neighbours who are unhoused, to smile and say hello, and maybe offer some food. “I think that those things need to be recognized too.” [end]

This in-depth article was made possible thanks to the community-minded readers who support this work.