As the Cowichan Valley transit strike enters its fourth month, community members who rely on public transit — and particularly those from marginalized communities — say they are feeling disconnected from the world as they struggle to get around to work, appointments, the grocery store and to socialize.

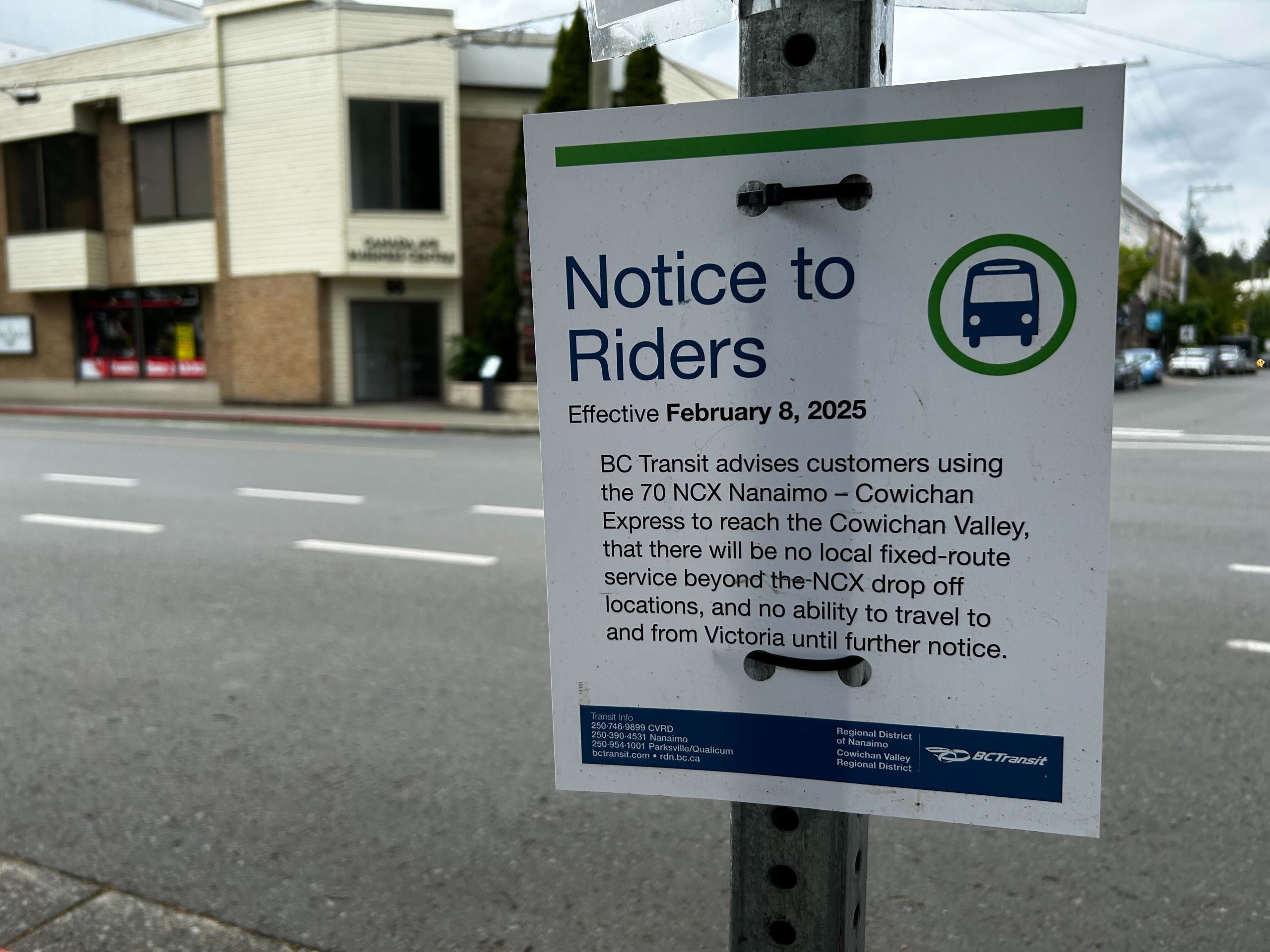

Unifor Local 114 and Unifor Local 333BC, the union representing 44 drivers, mechanics and cleaners, have been on strike since Feb. 8. They are advocating for wages similar to their counterparts in Victoria, better access to washroom facilities and more consistent breaks. Workers have since voted against a new contract with their employer, TransDev, and the strike reaches 105 days, there is still no end in sight. As a result of the strike, transit in the Cowichan Valley has been on hold, interfering with where and how people move through the community. HandyDart services are still available but only for medical appointments related to renal dialysis, cancer treatment and multiple sclerosis.

Doug Drummond, a driver with the union, said the public is starting to become “really angry” with how long the strike has gone on for. While he said the provincial government may step in and appoint a special mediator soon, a resolution is at least one month away.

“If the urgency is there, it happens really quickly, especially if the premier says, ‘get this thing done and over with’, so that’s a big hope,” he said.

Meanwhile, transit workers outside of the Cowichan Valley are keeping a sharp eye on what’s happening as collective agreements for transit workers in other regions will start to expire between now and the end of the year, Drummond said.

“We’re sort of leading the battle,” Drummond said.

TransDev, a company headquartered in France, is contracted by BC Transit to provide transit in the Cowichan Valley. In an email statement to The Discourse, BC transit said the “organization strongly believes in the collective bargaining process and hopes the two sides will reach an agreement soon.” BC Transit said it will update customers on the labour dispute between the union and TransDev when more information becomes available.

How are residents adapting to the transit strike?

Julie Fletcher is a single mother of two teens who relies on transit to get to work, appointments and for monthly shopping. Since the strike began, she has had to ask for help from family and friends and rely on taxis to get around.

“I feel shut in, isolated, depressed and hopeless due to not having the regular level of freedom I had when buses were running. I have even considered moving,” she told The Discourse.

When the buses come back, Fletcher said she hopes transit services could be expanded to run later in the evening since buses are the only option to get around after the taxis stop running at 5 p.m. Before the strike, most local buses stopped running at 8 p.m. While she is frustrated with lack of transit options during the strike, she said she “understands where the drivers are coming from and they deserve to be paid fairly and have bathroom breaks.”

As a tutor, Lia Versaevel works with students attending classes at Vancouver Island University’s Cowichan campus and said the strike is disproportionately affecting them.

“Many of the students I tutor have been unable to attend classes or other important appointments. Students are usually already struggling with finances and

they cannot afford taxis, if one were even to be found,” she said.

The Discourse recently held an in-person forum for International Women’s Day and attendees and speakers spoke to the lack of adequate bus services and taxis in the evening, something which they said impacts women disproportionately when it comes to safety.

Read more: Advocates call for wraparound care and community health centre for women in Cowichan

Another student at VIU’s Cowichan Campus, Lena Sorensen, said she moved to Duncan specifically because she is training to become a care aide. Since the strike, she has had to rely on her partner to take her to and from the Cowichan District Hospital and the Cowichan Campus where she is training.

“I really hope this strike comes to an end soon,” she said. “This should be deemed an essential service as not everyone wants to or can afford two cars.”

John Morton shared the story of his 90-year-old neighbor Shirley who is in a wheelchair and relies on the handyDart service to get to and from her appointments and to see her husband who lives at Cairnsmore Place, a long-term care facility in Duncan.

“The disruption has made it significantly harder for her to maintain this important part of her routine,” Morton said. “Even though Shirley is fiercely independent, her situation is a clear example of how vulnerable members of our community are directly impacted by the transit strike.”

Marginalized communities disproportionately impacted by the transit strike

Jeff Legatt, a grassroots disability advocate and founder of Disability Action of Canada, said he’s been giving rides to people he knows with disabilities for weeks, helping them get things as simple as their weekly groceries.

“The world has kind of closed down for people who are on disability,” Legatt said, noting that many residents are feeling the same limitations they felt during COVID-19, unable to maintain their regular routines.

Many have had to rely on friends and family for rides, or have had to pay out of pocket for specialized wheelchair accessible transportation like This Rides 4 U, a local company which Legatt says many people on disability can’t afford to use.

“They’re not being involved in the community as much as they’d like to be or normally are. A lot of disabled people, because they live in poverty, go on the bus and ride around and get to places. That’s part of their socializing,” he said.

In B.C. single people on disability can receive a maximum of $1483 a month and an unlimited bus pass through the BC Bus Pass Program or a Transportation Supplement of $52. Legatt said many people with disabilities choose to take the bus pass since they don’t own a car or can’t drive.

“When that’s taken away, it causes a lot more depression, causes a lot more disconnect from community and then you’re left behind,” Legatt said. “If you’re cutting that off, then you’re neglecting a very significant portion of society.”

Even when the buses are running Legatt said services could be expanded to better accommodate people with disabilities and seniors.

“We could use some more handyDart trips for both our disabled and our senior population. It’s tough to get appointments because they’re always so booked up.”

Legatt praised the strong relationship between transit workers and the regular riders from the disabled community, adding that people he’s spoken with don’t harbour any “ill will” toward the drivers and staff on strike.

Instead, he explained that frustration from the disabled community is directed at systemic issues – specifically that transit “isn’t perceived as an essential service” and that labour disputes are “allowed to continue and go on and on and on without resolution.” Legatt believes that the problem lies with how the system is set up, with BC Transit contracting services to third parties rather than the workers themselves who are “seeking well deserved and fair treatment.”

Tracy is a peer leader with the Cowichan Community Action Team who lives in Chemainus and relies on transit to get to work. She’s feeling the impact of the strike but said she has it far better than the unhoused folks she works with on a daily basis.

“They already have issues to begin with, so for them, it’s a major impact,” she said, noting that accessing treatment, getting to doctors appointments or even getting around to socialize has become more difficult. Many aren’t able to walk due to injuries or ongoing issues with their feet, leaving them feeling “stalled out” and unable to move as freely as they did before.

Tracy said she is thankful that she has friends in her life who can help her when she needs a ride but knows that “there’s an awful lot of unhoused people that don’t, and they’re on their own.”

“It’s a very not nice situation all the way around,” Tracy said.

Problems with rural transit

Todd Litman is the president of Better Island Transit, an advocacy group fighting for fair, equitable and affordable inter-regional public transit on Vancouver Island. He said rural transit is often underfunded by the province in favour of highways and improvements for road users and even when the buses do run, transit could be set up in a way to better serve people.

“They’re perfectly happy building highways, spending $2 billion a year to connect cities, but they don’t consider their responsibility to provide transit service for non-drivers,” he told The Discourse in an interview.

One solution, Litman said, would be to divert some funding from highways to inter-regional buses and rural transit systems and to reduce the amount of money that regional governments such as the Cowichan Valley Regional District would need to put forward to fund transit. Right now, local governments need to provide 50 per cent of the funds. He believes that 20 per cent would be more fair.

According to Litman, in a typical community, anywhere from 20 to 40 per cent of travellers either cannot drive due to a disability or aren’t able to afford a car. If you’re a low income person, a senior or a teenager, Litman said the transportation system “isn’t designed to serve your needs.”

“There are times in a person’s life where they can’t drive,” Litman explained, such as teenagers before they get licenses, seniors who fail driving tests or people experiencing financial hardship when “your car breaks down and you can’t afford to fix it.”

“Most people don’t think of that until they face that,” he said noting that this creates a political imbalance where those who need public transit are “disorganized and not politically powerful” while motorists wield more influence because “every time someone buys a car they expect the government to provide roads for their use.”

Litman isn’t surprised that there is a growing frustration among residents in the Cowichan Valley who, even when there isn’t a strike, struggle with lack of access to buses, taxis, ridesharing services or dedicated bike lanes.

“They should be frustrated because the current system is grossly unfair. It’s not responding to their needs,” he said.

He encouraged people to write to their MLAs and local regional district representatives to tell them that transit should be a priority and that the current system is unfair because “people who don’t drive don’t get their fair share of investments.”