For five summers, Camp Qwanoes in Crofton was a happy place for 16-year-old Ryland Racicot of Duncan. This summer promised to be the best yet, because he was going to participate in the camp’s Step-Out leadership program, a precursor to becoming a counselor-in-training.

But that all changed when Racicot was asked to sign a staff agreement that he and his family believe is in violation of his human rights. They say the agreement requires him to believe that abortion, homosexuality and premarital sex, among other things, are sinful. Despite having attended the camp many times as a camper, Racicot and his family weren’t aware of this staff agreement until Racicot had to sign it himself. They are upset that they are only now finding out about it and also question the legality of the agreement.

“I went to Camp Qwanoes for five summers in a row and there was nothing, no talk on the website or in person with the counselors about these contracts that they were signing,” he says. “If I’d have known that, I would never have gone.”

According to the camp, Racicot is welcome to return as a camper regardless of his beliefs, but can’t participate in the Step-Out program without signing the agreement, which is for staff as well as Step-Out participants and counselors-in-training. While Racicot has moved on to other summer plans, he and his family are speaking out in the hopes that other families can make an “informed decision” about whether Camp Qwanoes is the right fit for them, and that the camp makes its staff agreement more transparent and inclusive.

Read also: How does SOGI 123 show up in Cowichan Valley schools?

Student disheartened that he can’t participate in Camp Qwanoes program

A Grade 10 student at the Cowichan Performing Arts Academy, Racicot says he’s been hoping to participate in the Camp Qwanoes Step-Out program ever since he first started attending the camp. He put together a resume and solicited references, with the only remaining step being his signature on the staff agreement.

But when he saw the contents of the staff agreement, Racicot knew he couldn’t sign it because pieces of it didn’t align with his personal values. He showed it to his mother, Sylvia Webb, who immediately supported his decision.

It has always been important to her that Qwanoes is a Christian camp, but Webb says she and her son were shocked to learn that staff had to commit to uphold beliefs that consider homosexuality, extra-marital sex and abortion to be sinful, and that this doesn’t align with how she and her family practices Christianity. She also considers herself an ally of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, and says she believes the agreement is discriminatory. She wonders how it could be legal given the equality protections in Canada’s Human Rights Act, which was amended in 1996 to include sexual orientation as one of the act’s protected grounds.

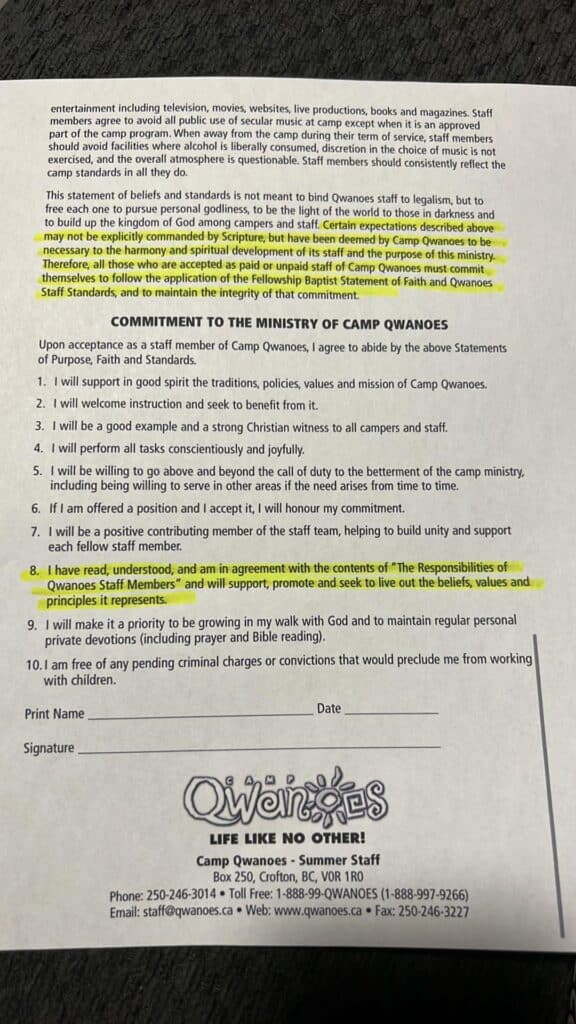

According to Webb, Racicot’s father, stepmother and stepfather also find specific sections of the four-page staff agreement objectionable. This includes the standards section that states staff members “are expected to be individuals that … refrain from practices which are condemned by God in the Bible.” This expectation is followed by a list of specific practices that includes abortion and “sexual sins” such as premarital sex and homosexual behaviour. In addition, “married staff members agree to maintain the sanctity of marriage and to take every positive step possible to avoid divorce.”

They are also concerned about a section on the first page of the agreement, where paid or volunteer staff must agree to maintain camp standards based on the word of God. It says, “Those who apply to Camp Qwanoes and cannot, in good conscience, agree to uphold these standards in their beliefs, conversations and lifestyles should seek another more acceptable situation.” The staff agreement additionally asks those signing it for a commitment that they agree with the contents of the agreement and “will support, promote and seek to live out the beliefs, values and principles it represents.”

Racicot says he doesn’t understand why it’s necessary that he needs to hold the beliefs cited in the agreement in order to participate in the leadership program. “It’s disheartening to know that I can’t do something I was pretty darn well dreaming to do for a good five-to-six years,” he says.

He is also bothered by the camp’s lack of transparency. He says it’s “absurd” that campers and their families aren’t informed about the staff agreement and that it isn’t easily accessible on the camp’s website.

Seeing her son so disappointed makes her “sad” and “worried,” Webb says. She expressed her concerns to Qwanoes executive director Scott Bayley during a 45-minute phone call. She says that while it was a good conversation, she came away from it concerned that people in leadership positions at the camp may be telling campers that things such as divorce and abortion are sinful.

“It’s 2023, I just assumed we were in a different place as a community in Canada and this situation was the first situation where I actually truly felt unsafe in my community,” she says. “It’s not just about homosexuality, it’s abortion, women’s rights, people that have left marriages because it’s abusive. It’s just not right.”

She explains that while some families might be fine with the agreement because it aligns with their beliefs or that those beliefs aren’t deal breakers for them, she believes there are others who will appreciate knowing what Camp Qwanoes staff have to sign in order to work there.

“We’re not saying we don’t love the camp. I love the camp. I absolutely love it. [Ryland] went there all those years. I’m just saying they are hiding behind campfires and canoes,” she says. “They are not allowing the community to make an informed decision. They’re just not.”

Camp Qwanoes executive director responds

Scott Bayley, executive director of Camp Qwanoes, declined to do an interview with The Discourse, citing concerns for Racicot and his family’s privacy. Instead, he emailed a statement from the camp and subsequently agreed to answer questions via email.

According to Bayley, more than half of the campers at Qwanoes come from families who don’t belong to a church.

“Our campers come from all backgrounds and they are all welcome at Qwanoes,” he said in an email. “We seek to treat everyone the same. We love all of our campers and it is extremely important to us that they all are made to feel valued, important and that they belong.”

He adds that the camp has a high retention rate, with many campers returning year after year and some who have attended Camp Qwanoes for 10 years in a row.

The Step-Out program is a Christian leadership program, with about 60 to 70 total participants in the various two-week sessions each summer, Bayley explains. He says through the program, “youth gain leadership skills, make new friendships, they learn to serve in various areas of camp and they grow in their Christian faith.”

Because it is a leadership program, Bayley notes that Step-Out participants are required to sign the camp’s staff agreement.

“As a Christian camp that is owned and operated by churches, we seek staff who share our beliefs … and people in our leadership programs have a role on our staff team,” Bayley’s email response says.

Camp Qwanoes was founded in 1966. When queried about how long the current staff agreement has been in place, Bayley replied, saying the expectation for staff to share the same Christian beliefs as the camp has been there from its inception.

On the question of whether the current Qwanoes staff contract could be in violation of the Canadian Human Rights Act, Bayley wrote, “Our understanding is that it is acceptable for us as a Christian non-profit organization to have staff agree to a staff contract. It would be very similar to what a church would expect when hiring staff.”

And regarding concerns raised by Racicot’s family, Bayley says, “We have greatly enjoyed having Ryland attend as a camper for many years, and we would love for him to continue attending as we have camps for up to age 18. We are going to review our website and look for ways where we could provide even greater clarity. It is noted that all of our social media accounts and our website clearly communicate that we are a Christian camp.”

Freedom of religion versus equality rights

Webb says that the family has been considering filing a complaint about the Camp Qwanoes staff agreement with the BC Human Rights Tribunal, but has decided for the time being not to go forward with it. She says they are hoping that the camp will “do the right thing” and revise the staff agreement to be more inclusive and be more transparent about what staff are having to sign.

Kyla Lee is a Vancouver attorney and second vice chair of the Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Community section of the Canadian Bar Association. She believes the family would likely have a strong case if they filed a complaint.

Human rights tribunals are increasingly having to balance competing rights from the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, such as equality rights and the freedom of religion, Lee explains. In 2018, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that law societies had the right to not accredit Trinity Western University’s law school over a required code of conduct deemed discriminatory to 2SLGBTQIA+ students. The law school subsequently made the code optional for students. This is an example of how something has to give way when two competing rights come up against each other.

“In that case, it was obviously the university,” Lee says.

But Lee explains the Camp Qwanoes staff agreement is slightly different from the Trinity Western code of conduct, in part because it’s a private camp and isn’t seeking “sort of a public institution status,” like the university was.

“When you have Camp Qwanoes being a religious-based organization, the tenets of the faith they express could potentially trump somebody’s sexual orientation,” she says.

According to Lee, a key legality question for the Qwanoes staff agreement concerns the imposition of a faith on another person. She says there is a notable difference between requiring staff to refrain from a particular behaviour and requiring them to agree to adhere to “statements of faith, purpose and standards,” such as the ones in the camp’s staff agreement.

“Requiring somebody to sign a statement basically saying that they’re not going to be gay, as opposed to saying that you’re not going to engage in a sexual relationship while you’re at the camp … that’s where I think the balance issue is going to come down if there was a complaint filed,” Lee says.

Retired pastor views “morality clauses” as part of a backlash against 2SLGBTQIA+ rights

To Reverend Brent Hawkes, a retired Toronto pastor and founder and executive director of Rainbow Faith and Freedom, the Qwanoes staff agreement is an example of a “morality clause” that is indicative of a growing backlash against 2SLGBTQIA+ rights.

“It feels like the hard work we’ve done to get equality for LGBT people is being undermined in the name of freedom of religion,” says Hawkes, who officiated Canada’s first gay weddings in 2001. He notes that homosexuality is not against Christian beliefs, just particular interpretations of it.

According to Hawkes, it’s becoming increasingly common for evangelical institutions to say they welcome everyone, without revealing that members of the 2SLGBTQIA+ community are not welcome in leadership positions.

“They’re not as upfront about their views because, frankly, they know that they’re controversial,” he says. “So it often only comes to light in exactly the kind of circumstances that you see in this case … when [Racicot] wanted to be involved in some leadership areas.”

He notes that the issue has come up with staff policies at some other Christian summer camps in Canada.

Hawkes argues that if a summer camp were to exclude staff based on race as opposed to sexual orientation, there would be an uproar. “What we have here feels like the LGBT community is being targeted in ways that would not be allowed in other circumstances.”

“I don’t want to demonize the people who push these morality clauses,” he says. “I hope they change their minds. I hope they do away with those clauses so that LGBT people and our families can fully participate and be fully involved in these organizations.”

In lieu of Camp Qwanoes, Racicot is going to do a two-week online camp this summer with the LeBlanc School of Acting. Webb says that when she and her son recently spoke to the owner of the acting school, it was clear that their values aligned with those of the acting school.

Racicot says that he has a friend who has attended the camp several times and has told him that it’s very diverse and inclusive. “I’m really excited to be part of that,” he says.