An organization formed to rethink how communities tackle doctor shortages in the Cowichan Valley is on the brink of shutting down, but is still pushing to fill urgent health-care gaps in Lake Cowichan, where the town’s only two doctors recently left or retired.

The Cowichan Valley Primary Care Society says more needs to be done to attract and retain primary care providers in the region and warns that without new funding and community support, the society could dissolve.

Founded in 2023, the non-profit set out to create a clinic owned and operated by the society, taking the administrative burden off of physicians and nurse practitioners. But the society has yet to find a willing clinic to be taken over and is now running short on funds.

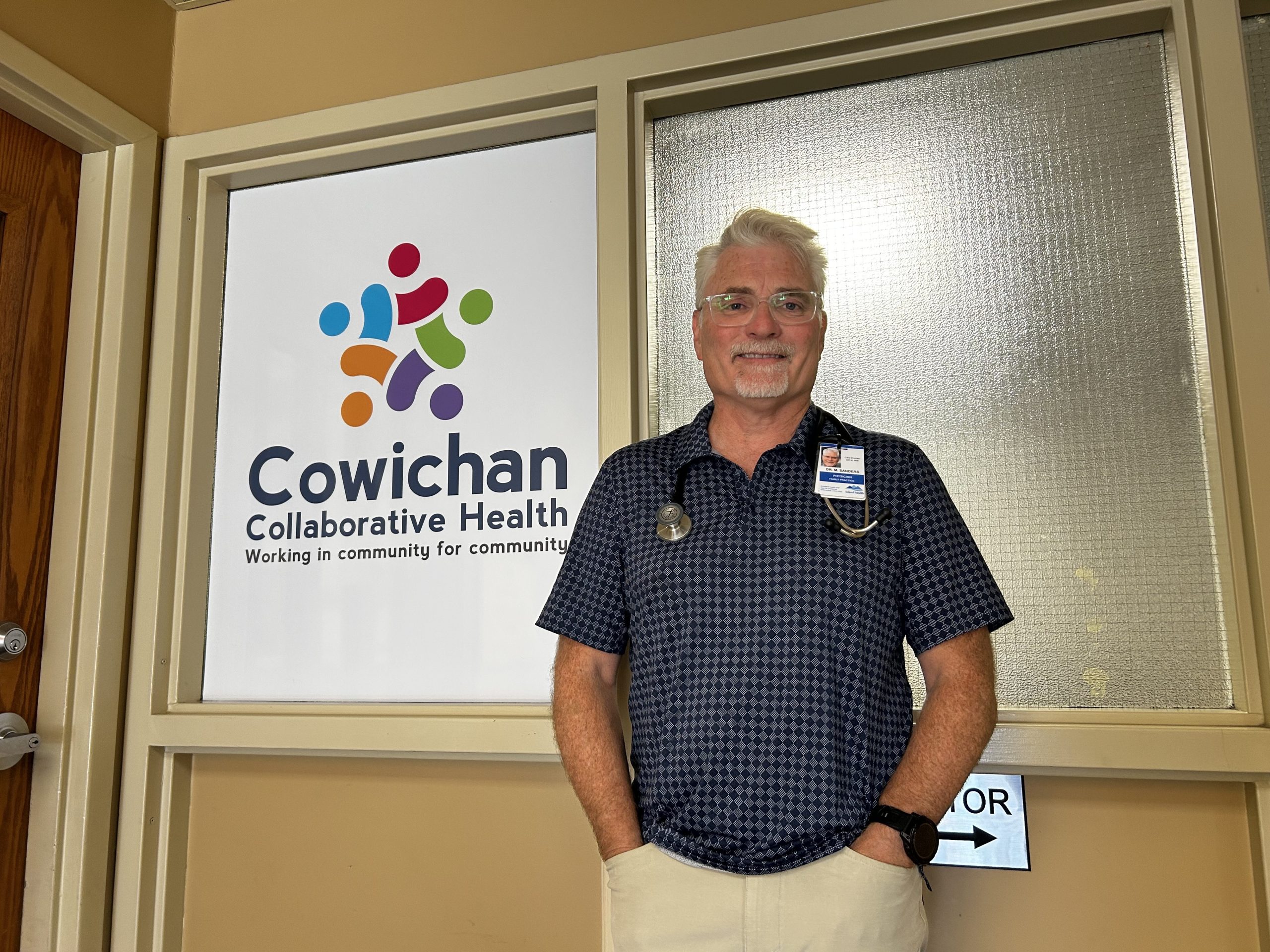

“This is kind of our last hope,” said Dr. Mark Sanders, a family physician and president of the society. “The focus of the nonprofit could shift and have a smaller goal.”

That smaller goal would be to support short-term solutions to the doctor shortage in Lake Cowichan, such as organizing rotating doctor coverage and providing incentives for doctors from out of town to see patients. But Sanders said funding for a project like that can be hard to secure.

“There might be a little bit of money to help support that and entice doctors to do shifts out there. This is all stuff that we’re tossing around as a possibility, but it is very possible, too, that our society ends up dissolving,” Sanders said.

Meanwhile, Aldea Maslak, a resident in the Quw’utsun Family Medicine Residency Program who lives in Honeymoon Bay, is promoting the lake town to new doctors she meets in hopes they might relocate to the region. The residency program brings cohorts of resident doctors practicing family medicine to the Cowichan Valley with an aim to see some of the residents stay in the community after the program.

Maslak has also established a memorial scholarship fund for Grade 12 students in Lake Cowichan who want to work in the health-care field and return to the area when they graduate.

As part of the residency program, she is developing a project to advocate for better health care access and envision what care could look like for Lake Cowichan residents in the future.

Maslak said the long-term solution to the health-care provider shortage in the region is to foster strong relationships with practitioners and create a positive culture that draws people in, rather than relying on individual contracts and financial incentives.

“That only goes so far,” she said. “People need to feel supported and valued so they can enjoy the work they are doing.”

One last hurrah for the Cowichan Valley Primary Care Society

Next week, Cowichan Valley Primary Care Society members hope to meet with local stakeholders in Lake Cowichan to propose a program that would bring in doctors from other parts of the Cowichan Valley to see patients who no longer have a family doctor. The society said it is important that the community is involved in creating the program rather than having a plan imposed on them.

“We’ve got an idea — we don’t want to impose it,” Sanders said. “If the town of Lake Cowichan doesn’t want it, sure. But if the town is interested, here’s how we might be able to try and run this.”

Lake Cowichan Mayor Tim MacGonigle said he has accepted the invitation to meet and plans to attend on behalf of the Town of Lake Cowichan.

“We as council are looking at every possibility to attract medical services to the west Cowichan area,” he said. “Including collaborating with the local First Nation and adjacent electoral areas.”

Invitations to the meeting went out on Tuesday, Aug. 12 according to Sanders. He hopes that other town councillors and area directors from the Cowichan Valley Regional District will also attend.

The society has a small pool of funds that have been collected through grants from local governments and individual donations, but more would be needed to run the program and to compensate doctors for their travel and time. Sanders estimates the cost at roughly $1,000 per week.

“We either need a big carrot or we need a series of small carrots,” he said. “The idea is totally doable, but you just need to make sure that people are compensated for that.”

Sanders said the messaging he’s received from the Ministry of Health is that there isn’t funding available to support efforts to fill gaps in health care in Lake Cowichan and compensate doctors for “bridge work,” which would include costs for travel.

“They [the Ministry] have a lot of needs, and the messaging that I’ve received is that there just isn’t funding right now for anything extra to support what’s going on out there,” he said.

In a statement to The Discourse, the province’s Ministry of Health said Lake Cowichan has been identified as a priority region for recruitment.

“The local Cowichan Valley Division of Family Practice and Island Health are actively recruiting family physicians and nurse practitioners to ensure patients in Lake Cowichan receive the care they need,” the statement said.

The program proposed by the Cowichan Valley Primary Care Society would also work to create a list of care providers who are willing to travel out to Lake Cowichan and review it quarterly to ensure that there is a rotating number of providers who can see patients in Lake Cowichan. But Sanders said it’s not the best long term solution.

“The best long term solution would be to have a permanent physician — physicians that get to know the families and people of Lake Cowichan,” he said. “But this could be a bridge and could be a support to balance providing some of the care for those people in need, especially those that can’t travel.”

Easing the burden on new doctors

The Cowichan Valley Primary Care Society was originally envisioned as a non-profit that would take over the administration of clinics, freeing doctors to focus on treating patients.

The society would manage recruitment of medical office assistants and support staff, handle payroll, order supplies and oversee accounting and bookkeeping — tasks that aren’t necessarily part of a doctor’s job but fall to those who operate clinics.

“Family doctors having to be lease-holders and managers is not appealing to new grads,” reads the society’s website. “Many of these doctors do not want to take on the enormous administrative burdens of owning and running a business, especially in these uncertain times, opting to do other work rather than committing to looking after a panel of patients.”

Sanders said it has been difficult to convince doctors used to running their own practices to give up autonomy, even when their businesses were going to fail. He said many physicians were reluctant to join a non-profit model where an outside board would have influence, noting that “physician autonomy” is so valued among established practitioners that very few are likely to enter such an arrangement.

By contrast, new providers are much more willing to work under a non-profit model, according to Sanders.

A 2025 study published in Canadian Family Physician found that administrative burdens — such as lack of compensation for non-clinical tasks — negatively impacts physicians’ well-being and reduces the time they have for direct patient care, leading to burnout.

Even for Maslak, it wouldn’t be sustainable to take on all of the patients who no longer have a family doctor in Lake Cowichan after she graduates. She estimates that six physicians would be needed to properly care for the communities of Lake Cowichan, Mesachie Lake, Youbou and Caycuse.

Her goal is to remain in Lake Cowichan and help lay the groundwork for other physicians to relocate and open up practices, while still dedicating part of her time to clinical work.

“I wanted to try and do this career to help fill a need in the community that I saw and figure out how to build something bigger and sustainable with more people,” she said.

A long-term view of health care in the Cowichan Valley

Sanders has recently opened a new clinic not related to the society located in the Ingram Building in downtown Duncan at 149 Ingram St. called Cowichan Collaborative Health. He said the clinic focuses on team-based care, where he and another physician along with other health-care professionals — including nurse practitioners, a pediatrician and clinical counselor — operate under one roof to care for patients. The clinic also has space for practitioners to provide part-time family medicine. Sanders said shifting patient care in the Valley from the traditional model to a team-based one could help attract new doctors who might be reluctant to take on the administrative burden of owning and operating a clinic.

“My vision has always been team-based care, and to kind of expand the model and change the model with this changing landscape of workers. I felt that if you leverage teams, you could serve more people,” he said.

The Canadian Medical Association has called on provincial governments to establish primary care teams for half of Canadians in the next five years. It says the benefits of team-based care include better continuity of care for patients, a smaller patient load for practitioners and coverage for care providers when they need time off.

Sanders said providing doctor coverage in Lake Cowichan would be a long-term investment for health care in the Valley as patients would visit the emergency room less, have shorter hospital stays and ultimately put less pressure on the system.

He also sees the Quw’utsun Family Medicine Residency Program, which he is on the faculty of, as a solution for the doctor shortage. Residents often choose to stay in the areas where they do their training, he said.

“The program is really going well. We currently have eight residents. There has been a definite suggestion that at least some of them want to stay and work,” he said.

Maslak said that in addition to herself, she believes several other residents from the program will continue to practice in the Cowichan Valley. She plans to split her time between working at various Indigenous health clinics and seeing patients in Lake Cowichan.

But she also noted that more supports and incentives — other than financial ones — are needed to convince doctors to stay in smaller communities. They need to know that they can build community and participate in it and have the support of other doctors in the region.

Having lived in Lake Cowichan since 2012, Maslak said she understands the challenges working in a more remote community poses compared to more populated areas like Duncan.

Compared to Duncan, Lake Cowichan has fewer services, amenities and activities for families, making it a harder sell for new practitioners. She said the same pool of potential recruits for Lake Cowichan could be drawn to other areas in the Valley instead.

“It’s really nice in the summer, but there are fewer resources and no other doctors here to support you,” she said.

Maslak said that after she graduates and begins practising in Lake Cowichan, she can apply to become a preceptor — a teacher and clinical supervisor for incoming residents — to help build relationships with new doctors.

“I know we need to do some stopgap measures here and help the people who are left without care right at this moment, but for it to really work, I think we need to think big picture and long-term,” she said.