Across the province, overdose deaths fell last year, according to the BC Coroners Service.

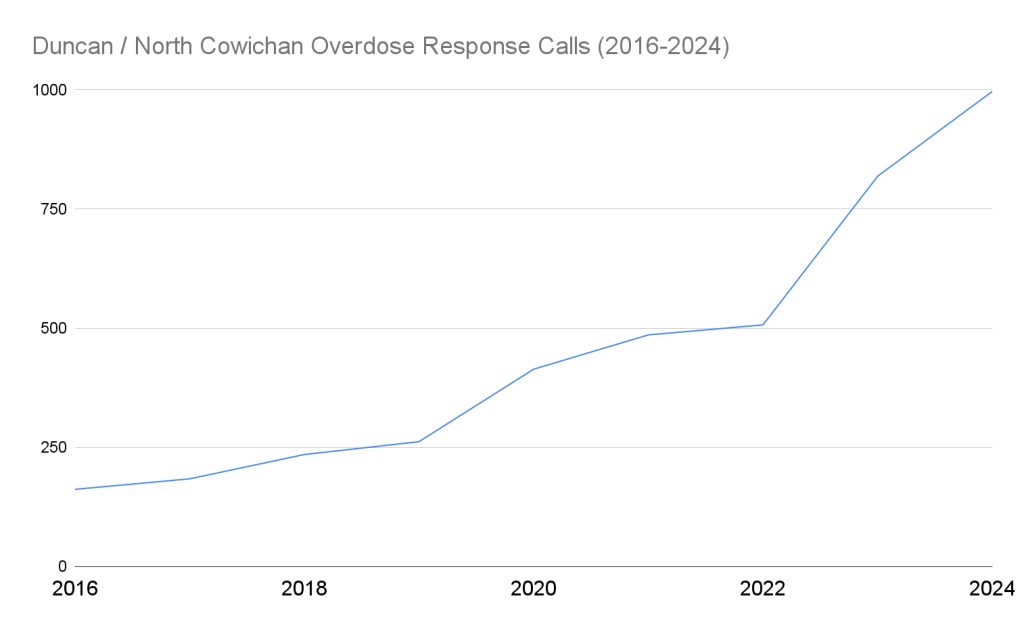

Still, in the Cowichan Valley, overdose and drug poisoning calls stayed relatively stable and even increased slightly, rising from 819 to 997 between 2023 and 2024 in Duncan.

BC Emergency Health Services (BCEHS) also released its 2024 statistics for overdose response calls in B.C. While total response calls fell four per cent across the province last year, calls in Duncan and North Cowichan increased. When looking at the whole Cowichan Valley, just over 90 percent of all overdose calls attended by BCEHS in 2024 originated in Duncan and North Cowichan.

Compared to the entirety of Island Health, which saw an average decrease in overdose response calls of five percent, Duncan and North Cowichan were well above that, showing an increase of 21 percent.

Other larger centres like Nanaimo have seen a drop in overdose response calls from 2,136 in 2023 to 1,525 last year, a 29 per cent decrease.

“In all substance use related harm, there’s a gradient from South to North Island, by and large, but the very local factors, especially in smaller communities, are harder to really assess as to what’s contributing to them,” Island Health Chief Medical Health Officer Dr. Réka Gustafson said in an interview with The Discourse.

Gustafson says Island Health is still committed to providing overdose prevention sites and medical care to people who need it but stressed that no one service is the answer for everyone.

“One of the things that I find in our conversations is that we focus on one intervention versus another, as if one is to be the answer. No, we actually need them all at the scale of the issue,” she said.

How are emergency services and local groups responding to the increase in overdose response calls?

BCEHS couldn’t directly comment on the trend but said they are looking at ways to connect patients who have experienced an overdose with community services.

Throughout the toxic drug crisis, they say paramedics have become community advocates “encouraging people who use to not use alone, to access overdose prevention sites, and encourage friends and family to have access to take-home naloxone kits.”

BCEHS also says its harm reduction initiative, the Assess, See, Treat and Refer Pathway, has seen some success since its launch in June 2022. The program sees paramedics refer consenting patients who have experienced drug poisoning to outreach services in their community rather than going to a hospital.

As of December last year, it says the program has connected 754 patients to treatment, safe supplies, housing and peer support across the province.

According to BCEHS, people who do use alone are encouraged to use the Lifeguard Connect app by responding paramedics.

The free app is a harm-reduction service that uses a timer to automatically alert BCEHS 9-1-1 dispatchers when a person using drugs alone is unable to turn off the alarm.

“Due to stigma, some people are not comfortable telling someone else they are using opioids or other substances, but using while alone is extremely dangerous,” Cailey Foster with the Cowichan Community Action Team told The Discourse. “With virtual tools, people can take steps to stay safer, even if they are alone.”

Foster said that while the Lifeguard app is a vital tool for people using alone, most people the community action team works with don’t have a phone and are more likely to use a space like the Cowichan Valley Wellness and Recovery Centre.

The Community Action Team is currently waiting for a presentation on the overdose numbers before taking a closer look at the results and outcomes in the community, it said in a statement to The Discourse.

What is North Cowichan doing to reduce overdoses?

The data for overdose response calls from BCEHS groups North Cowichan and Duncan into one area. Outlying communities like Lake Cowichan, Shawnigan Lake, Cobble Hill, and Ladysmith have their own entries.

North Cowichan Mayor Rob Douglas says the municipality doesn’t have many options to reduce drug overdoses directly, since municipalities do not govern health care or housing.

“One area where I think we can really step up our efforts is putting that pressure on the provincial and federal government to provide us with the resources to address these issues,” he said in an interview with The Discourse.

Douglas says the idea of a “four-pillar approach” has come up in their discussions with the province, but has not been formalized in any municipality documents. He compared that approach to the City of Vancouver’s four-pillar strategy of harm reduction, prevention, treatment and enforcement, a framework that was also briefly adopted by the federal government.

In response to the overdose crisis more than two decades ago, Vancouver became the first jurisdiction in Canada to offer a sanctioned overdose prevention site with support from the federal government. It also increased policing over the open drug market and public education strategies.

The framework’s purpose, as written, was to persuade higher levels of government to take action, restore public order, reduce drug-related harm to communities and individuals and establish a single accountable agent to coordinate the City of Vancouver’s efforts.

While the four-pillar strategy has been in place for over 20 years in Vancouver, a recent study that interviewed drug policy stakeholders called it “structurally dysfunctional in working towards a common goal.”

In recent years, Douglas said the municipality made more investments in the enforcement pillar, “ensuring that the RCMP is putting a real focus on some of these issues” and building a new $48 million RCMP detachment.

“What we’ve been arguing at North Cowichan is we’ve really got to get back to taking this four pillars approach, rather than focusing on one or two components of it, really take that more encompassing approach to address the drug crisis and the challenges with mental health,” he said.

North Cowichan has also focused on advocating for the province to build a treatment facility and pitching to service providers like Together We Can, which runs treatment facilities in Vancouver and Victoria, that there is a need for one in the Cowichan Valley.

Douglas said the two main hurdles for service providers expanding treatment programs to the Cowichan Valley are the lack of government funding and the space to house the program.

Ultimately, he said, it’s up to the province to decide whether to make those “necessary investments” in the community.

Province ends take-home safer supply

This week, B.C.’s health minister announced that the people using the Prescribed Alternatives Program will have to take medications under the supervision of health professionals.

Prescribed Alternatives Program, or safe supply, is a form of treatment that provides daily prescription medicine for people addicted to opioids including fentanyl. They are used to reduce withdrawal symptoms and cravings and stabilize patients.

Under the new rules announced by the province on Wednesday that came into immediate effect, patients who are receiving this treatment will have to travel to a pharmacy multiple times a day to take their doses under the supervision of a healthcare professional.

The ministry says it is implementing these changes to ensure that prescribed opioids are used only by individuals with a prescription and “remove the risk of these medications from ending up in the hands of gangs and organized crime.”

Since last year, the Ministry of Health’s Special Investigative Unit has been investigating pharmacies suspected of contributing to the diversion of safer supply, the province said in a statement.

Interim Green Party leader Jeremy Valeriote says that while there are concerns about diversion, the move “raises serious questions about effectiveness and unintended consequences.”

“Restricting access to regulated pharmaceuticals will not stop people from using drugs; it will simply push them toward far more dangerous options. This government has a responsibility to protect public health, and this policy risks doing the opposite,” he said.

Moms Stop the Harm, the organization of mothers who have lost children to unregulated toxic drugs, said in a social media post called the policy change “devastating.”

“This program has saved and stabilized the lives of many people, who will now be at risk of dying. Witnessed options aren’t possible in almost every jurisdiction, especially those who live in rural and remote, including Indigenous communities.”

Along with changes to how prescribed opioids are taken, the province says it will also change the fee structure for pharmacies to stop what it calls “illegal activities” like offering “kickbacks” to retain or attract new patients. Kickbacks occur when pharmacies offer cash payments to clients for filling prescriptions at a particular pharmacy.

“Any such program will have a risk of diversion. So do we need to monitor that. But we also need to recognize that people are currently dying from an illegal toxic supply,” Gustafson said, “and the reason people are dying is because the drug supply is toxic, and the reason it’s toxic is because it’s illegal.”