Kelly Black is a researcher, writer, historian and collector of books and has taught B.C. and Canadian history at Vancouver Island University. What questions do you have about Cowichan Valley history? Send us an email and we’ll do our best to tackle them.

Thomas Quamtany — sometimes called Tomo Antoine — didn’t always have one arm. But when historian W.H. Olsen tried to answer the question of how the Hudson’s Bay Company carpenter, interpreter and guide lost his right arm, it illustrated what happens when one historian’s interpretation shapes the telling — and retelling — of an important moment in Cowichan’s colonial history.

Writing in his 1963 book Water Over the Wheel, Olsen suggested Quamtany was shot by a Quw’utsun Chief in August of 1856.

The shooting led to a display of gunboat diplomacy and colonial violence on Quw’utsun lands. But Olsen’s placement of Quamtany at the centre of the shooting, repeated by historians many times since, has proven to be incorrect.

Thomas the interpreter

Born around 1824 at Fort Vancouver (present day Vancouver, Washington) to a Haudenosaunee father and Chinook Indian Nation mother, Thomas Quamtany was one of many people of mixed ancestry integral to the operations of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC).

The Haudenosaunee, or Iroqouis as they were then called, were skilled carpenters, boatmen and hunters and were essential to the fur trade on the Pacific Slope — regions in the Americas that are west of the continental divide.

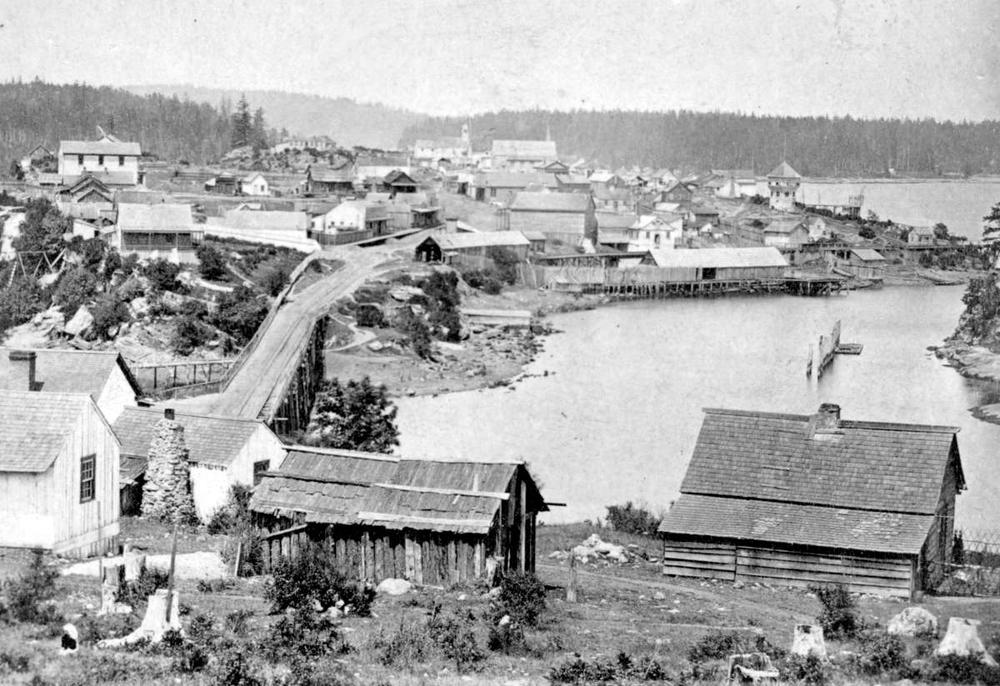

It was Quamtany and other Haudenosaunee who constructed the buildings of colonial Nanaimo, including the city’s landmark Bastion. But in Iroquois in the West, historian Jean Barman notes that, “they are absent in histories of Nanaimo … It is as though Iroquois never existed, which from the perspective of those doing the writing, was the case.”

Through the late 1840s, Quamtany worked at Fort Victoria performing various tasks such as well digging, horse taming and building. His ability to converse in several First Nations languages made him a go-to person for colonial governor and HBC chief factor James Douglas, who referred to him as “Thomas the Interpreter.”

As an interpreter and guide, Quamtany was present at a number of critical events that shaped the colonization of Vancouver Island.

Read also: Finding ‘Cowichan’: How colonization redefined local landscapes

A misinterpretation of facts

On Aug. 22, 1856, a man was brought to Fort Victoria from the Cowichan Valley suffering from a gunshot wound to the arm. The man had been harassing Quw’utsun People and was ambushed and shot by a young S’amunu chief named Tathlasut for interfering in his upcoming marriage.

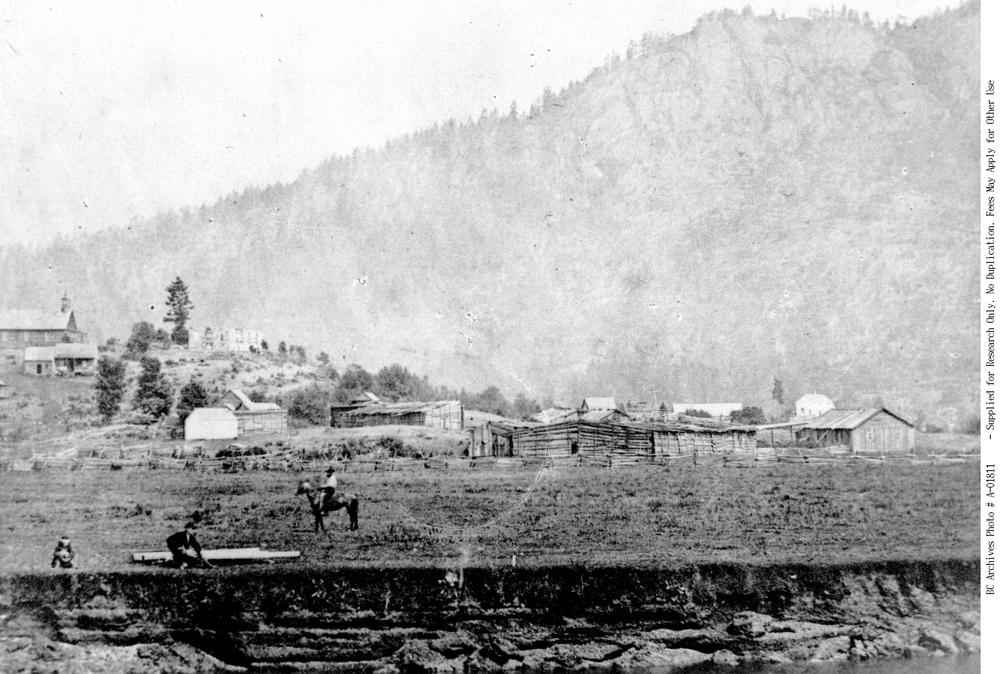

Governor Douglas detailed the event in his correspondence with colonial officials in London and referred to the wounded man as “Thomas Williams.” One week after the shooting, the governor responded by arriving in Cowichan Bay with two gunships and a force of nearly 500 men. After the ships fired upon the Quw’utsun village, Tathlasut was captured, put on trial and executed.

Writing in 1963, W.H. Olsen suggested that “Williams” — the man who was shot — was actually Quamtany, his name changed by Douglas to sound less Indigenous in order to justify the use of force to colonial officials reading the correspondence.

Unfortunately, Olsen’s explanation does not hold up to scrutiny.

Thomas Quamtany couldn’t have been shot because he was at work in Nanaimo when the shooting took place on Quw’utsun lands. Evidence for this comes from an HBC Nanaimo Memoranda dated Aug. 25, 1856.

“Men at their usual employment. 11:15 a canoe arrived with a Despatch from the Governor ordering Thos. Quantomy to proceed at once to Victoria to act as interpreter, a white man having been wounded by a [Quw’utsun person],” the memoranda says.

The assertion that Thomas Williams and Thomas Quamtany are two different people is clearly backed by the research of historian Graham Brazier, who has been “on the trail of the one armed man” for more than two decades.

Brazier focuses on Douglas’s correspondence and the initial uncertainty about the identity of the man who was shot, as well as other correspondences in which Williams is described variously as a white man and a settler.

Additionally, Brazier refers to the correspondence of both an HBC chaplain who states that the victim was a white man who recovered, and a letter from a woman named Annie Deans which describes a man shot by Tathlasut, who did not lose his arm.

Brazier published his findings in 2000, but Olsen’s narrative about the one-armed man was already well-established — repeated online, in newspapers and in books.

How did Thomas Quamtany lose his right arm?

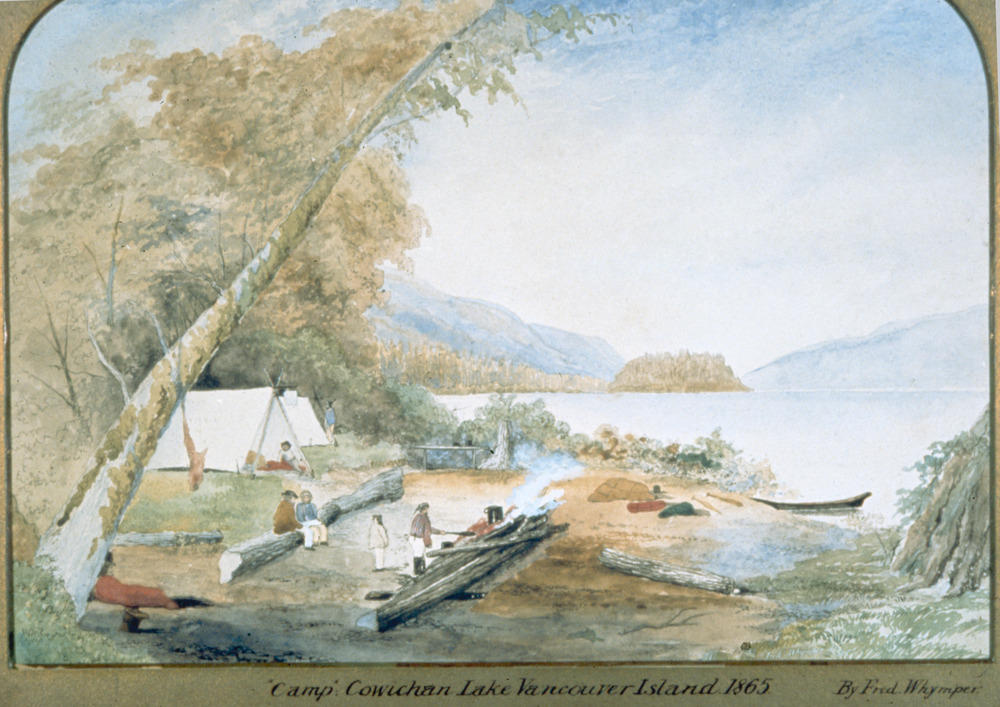

As an interpreter, Thomas Quamtany was present during the 1856 incursion into Cowichan Bay; by the 1860s he was living in the Cowichan Valley at Cherry Point. His knowledge of Vancouver Island was in demand and he was an important member of several explorations for trade routes and precious minerals.

Robert Brown, leader of the Vancouver Island Exploring Expedition of 1864, asked Quamtany to guide his team and later published a recollection of the man.

“During all our long conversations none of us had ever reason to regret the day when he joined our party, and to this hour One-armed Tomo, the swarthy vagabond of the western forests, is only remembered as a hearty fellow — a prince of hunters and doctor of all wood rafts — whose single arm was worth more than most men’s two,” the recollection says.

While we now know that Quamtany was not shot in August 1856, we are still left with the question that Olsen tried to answer: How did he lose his right arm?

HBC officials recorded various kinds of employee sickness in their journals and letters, so it seems likely that an amputation would be documented.

At Fort Victoria in 1851, HBC doctor John S. Helmcken amputated the arm of employee Charles Fish after it was blown apart by the misfiring of a cannon. Fish did not survive, reflecting the 50 per cent survival rate for amputation at the time.

The first archival reference which attributes “one arm” to Quamtany comes from the Nanaimo HBC Memoranda for Nov. 21, 1856. “One armed Toma, [sic], McCarthy and Tahooa engaged at the mill,” it says. He must have lost his arm before 1856 — but when, and how?

The short answer is, we don’t know. Brazier, however, is still on the trail. He offers an 1843 journal entry from HBC Fort Simpson (near present day Prince Rupert) as a possible answer.

On one of its regular trips between fur trade posts, the HBC steamer Beaver departed Fort Simpson on May 23, 1843. When the ship returned a cannon salute from the fort, one of the men on board had his hand blown off, requiring amputation. It seems the man survived, but the journal entry does not provide a name.

We do know that Thomas Quamtany struggled with alcohol, the trauma of his amputation a likely contributing factor. By the time he joined Brown’s 1864 expedition he had already been jailed and later acquitted in the death of his Quw’utsun wife, allegedly committed during an alcohol-induced fight.

Much like the circumstances surrounding the loss of his arm, we don’t really know when or how Quamtany died. One settler recollection found in the Nanaimo Archives claims he was ambushed and killed in 1868. So far, there is no other evidence to support this claim.

Even in the 19th century, Thomas Quamtany was an infamous Vancouver Island character. The work of history is the work of retelling and revision, and Olsen’s 1963 stories about “one armed Tomo” — complete with imagined illustrations of his likeness — further contributed to our present-day narrative about his life.

Connecting the 1856 shooting of Thomas Williams to Quamtany’s amputation made for a good story and it has been repeated many times since. However, today, we know that the two events are separate — and so the work of retelling and revision continues.