Following a series of break-ins at downtown Nanaimo businesses in January, a headline quoting a Nanaimo RCMP officer said “85 per cent of all crimes are drug related” and caused some people to question where the data came from.

In an email obtained by The Discourse responding to a question from North Cowichan Cop Watch if the claim could be supported, Nanaimo RCMP constable Gary O’Brien wrote that “there is no empirical evidence that I can present to you other than my 35 years of policing and having worked with hundreds of police officers, and spoken with dozens of dispatchers, home owners, addicts and criminals.”

“I think it’s a real generalization,” Pam Kent, the interim director of the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction told The Discourse. “I think it’s a dangerous statement to put out there. You want to be able to back it up if you’re going to say it.”

Also in January, Nanaimo Mayor Leonard Krog spoke at a forum in Vancouver on public safety saying “we are in the midst of a mental health addictions, trauma and brain injury crisis. It manifests itself in homelessness and the petty crime associated with dealing with your drug addiction.”

How much crime can be attributed to drug use is an important question that has been debated regularly by politicians, police, harm reduction workers, business owners and advocates. But the debates are often coloured by anecdotal experiences in specific neighbourhoods.

While some academic studies have found a correlation between violent crime and substance use — particularly alcohol use — experts, including some police officers, say the solution to this problem isn’t found through the criminal justice system. Instead, they call for more robust health care supports and policies that reduce the prevalence of drug and alcohol use in the community.

“At the community level, the prevalence rates are high for these substances, and that contributes to crime,” Kent said. “So can we collectively find ways to reduce prevalence rates and make sure people have access to the continuum of care, so that crime doesn’t have to come into play?”

VIU criminology professor says drug use should be treated as a health issue

Lauren Mayes is a criminology professor at Vancouver Island University who teaches a class on the relationship between drugs and crime. She also helps run the Inside Out program, where students from VIU learn with inmates from the Nanaimo Correctional Facility’s treatment-based unit.

“Drug use is both a criminal justice issue at this point and a healthcare issue. It could just be a healthcare issue, but we choose to use the criminal justice system to respond to it,” she told The Discourse. “That only makes things worse, instead of having more resources going towards a health-care oriented response.”

Living downtown, Mayes has seen first hand the impact of open drug use on her community.

“My own partner has found two people dead out on the street around our house,” she said. “That impacts you on a real level.”

She has also lost students that she teaches to drug overdoses and says that while she wants to minimize harm to other people in the community she’s less concerned with criminal behavior by people who use drugs and is “more concerned with them dying.”

Alcohol leading contributor to drug-related violent crime

A 2023 study by the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction found that substance use was related to 45 per cent of violent crime by males and 49 per cent by females who were incarcerated in federal prisons in Canada. For non-violent offenses, substance use was linked to 34 per cent of crimes committed by males and 29 per cent committed by females.

Of that, alcohol use was attributed to the largest number of violent offenses — 27 per cent (males) and 26 per cent (females) — while also contributing to 12 per cent and six per cent of all non-violent offenses.

All other substances combined contributed to 18 per cent of violent crimes by males and 23 per cent of violent crimes by females. It also found that 23 per cent of non-violent crimes for both males and females were attributable to substance use other than alcohol.

The study included how much crime was done while intoxicated, how much was due to trying to get money to pay for drugs and alcohol and how much of it was systemic to participating in the illicit drug market, such as assaults for drug debts. Offenses that were fully attributable to alcohol or drug use, such as impaired driving or drug charges, were excluded from those calculations.

Editor’s note: The study did not look at the identified genders of the offenders, men and women, and only had data for binary sex available. To ensure accuracy we have kept that wording.

Data from Statistics Canada shows that the non-violent crime severity index in the city of Nanaimo was significantly higher in the late 1990s and early 2000s, before falling between 2006 and 2013. Since then it has gone up and down over the years with a spike in 2019 and then falling in 2020 and going up slightly in 2022 and 2023.

The crime severity index is a measurement that gives more weight to more severe crimes and is considered a better representation than just the number of crimes.

Nanaimo’s violent crime severity index has been more volatile but shows an overall trend of falling between 1998 and 2015 and has since steadily risen to record levels.

Chart showing crime severity indexes for the city of Nanaimo between 1998 and 2023. Chart by Mick Sweetman / The Discourse.

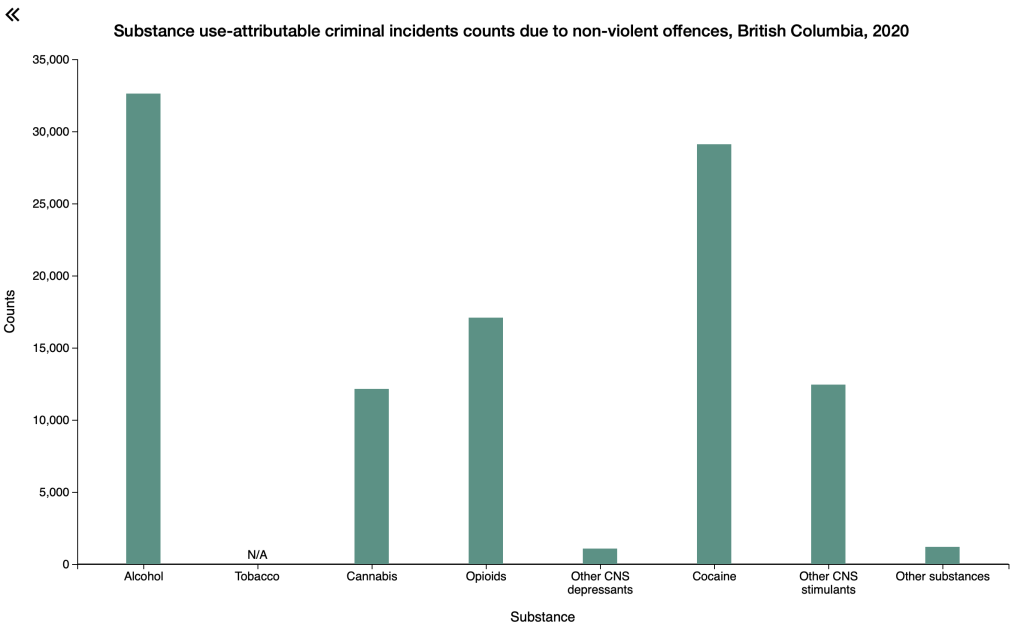

Using crime data from Statistics Canada, researchers developed a methodology to estimate how much of it could be attributed to substance use. They found that alcohol was the leading contributor followed by cocaine and opioids for drug-related non-violent crimes in B.C. in 2020.

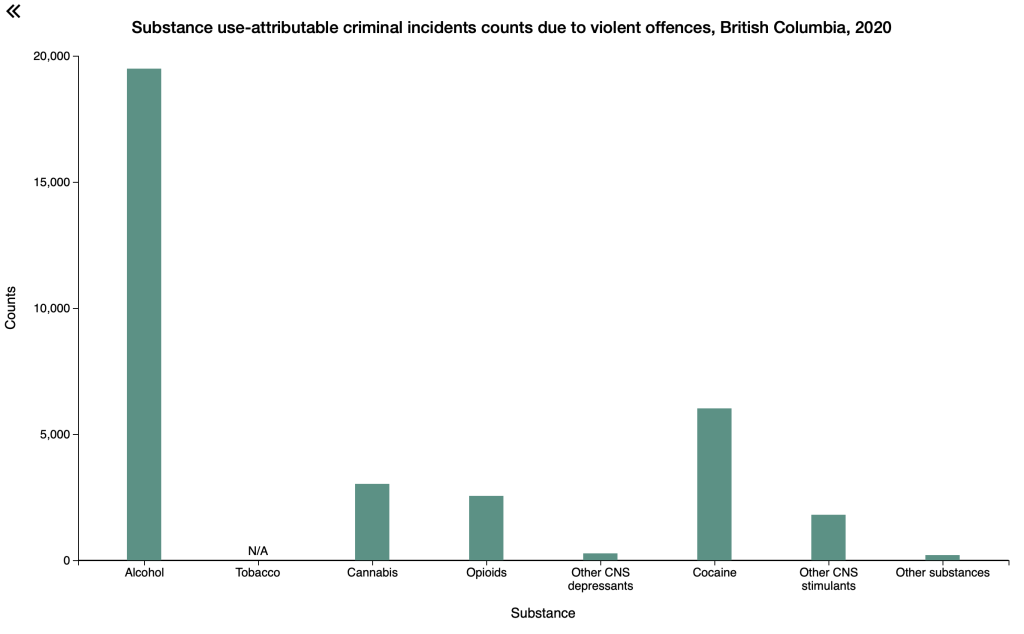

For violent crimes, an estimated 33,357 crimes were attributable to all substances, with alcohol being by far the leading contributor.

Kent, who was principal investigator for the Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms Report, says there may be some regions where there is a concentration of crime but it’s important to look at the impact of drug and alcohol use broadly across all crimes.

Alcohol often not included when talking about drug-related crime

Kent highlights alcohol as a major contributor to crime, but says it is often not considered a drug due to it being legal to sell and consume.

“Alcohol is by far the greatest contributor to costs for society in Canada,” she said.

“Obviously we have a lot of harms related to opioids, but the overall costs and harms are significantly less than alcohol.”

The high cost of alcohol in terms of crime, as well as public health, is largely due to the widespread use of it. Kent said close to 80 per cent of Canadians use alcohol and that is what is driving its high costs to society.

In 2023, the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction published risk guidelines for alcohol and physical health that range from no risk to high risk. No risk was zero drinks a week, low risk was one to two drinks, moderate risk ranged from three to six drinks a week and high risk was seven to eight drinks or more a week. The possibility of poor health outcomes increases with more alcohol use, according to these guidelines, and can lead to more strain on the health-care system.

“The point is the awareness that less is better and that alcohol is linked with harm,” she said. “There’s cancers associated with alcohol, other health harms and violence and crime.”

How to reduce drug-related crime

Instead of focusing on responses to the crime caused by drugs, Kent would like to see policy makers work on reducing the prevalence of drug and alcohol use.

To do this, Kent supports a broad range of strategies to help reduce the prevalence of drug and alcohol use and its impacts on society.

“You need strong treatment approaches, you need harm reduction, you need prevention across that continuum. I do believe that in itself will help to reduce crime rates because it’s all linked. If you can reduce the prevalence of substance use in society, crimes linked to substance use are going to decrease.”

Mayes points to the high rate of child poverty in Nanaimo and said adverse experiences in childhood can lead to future substance use as well as criminal behaviour.

In 2022, the rate of child poverty in Nanaimo was 17.4 per cent with the highest rates for child poverty concentrated in downtown and south Nanaimo. An estimated 3,460 children in the city lived in poverty according to the 2024 BC Child Poverty Report Card.

“The level of trauma that is experienced is, unfortunately, high. There’s more we need to do on the front end to try to minimize the amount of trauma that children are exposed to,” she said. “We need to better support children and families. Whether that’s school-based interventions or culturally sensitive early childhood interventions.”

Police perspectives

An article published in the Harm Reduction Journal in 2022 looked at the perspectives of police officers on the system’s impact on people who use drugs. It found that officers described the criminal justice system as failing to prevent drug-related crime.

One officer told researchers that jailing people who have committed “minor property crime to fuel their drug habits” was “a waste of the system. They don’t get clean in prison, I know that. They get drugs easily in prison. And they become embedded in the gangs that control those prisons.”

Another officer questioned the effectiveness of arresting people who use drugs.

“I do understand that alcohol and drug addiction is a health concern and health issue, I just wish there was more from the health side of things to help with this problem.”

In Nanaimo, in addition to the RCMP, the city’s bylaw department also employs Community Safety Officers to “engage with vulnerable citizens, including people experiencing homelessness, addiction and mental health concerns, to assist in the coordination of appropriate social, health and enforcement responses,” according to the City of Nanaimo website.

“They’re doing a fantastic job,” said Mayes, who co-chairs Nanaimo’s Acute Response Team which works to help identify people living at elevated levels of risk and provide services to prevent harm or the need for police intervention.

“They sit around the acute response table and they clearly have established some really strong relationships with people who are pretty substance-affected and roughly housed.”

The Nanaimo RCMP also have a “Car 54 program” that partners their mental health liaison officer with a community nurse from Island Health to respond to people who are experiencing a mental health or substance use crisis.

Mayes said the RCMP are sensitive to the issue and acknowledges that “it is a difficult thing to police. It’s a difficult thing to see the same people day and day out. So, they’ve recognized the need to do things differently.”

Nanaimo RCMP spokesperson Gary O’Brian declined a request for an interview for this story as it did not relate to a specific file.

Island Health also operates a number of community healthcare teams in the city such as the Community Outreach Response, Substance Use Services Outreach and Primary Care Outreach.

The overall message that Mayes stressed is that the view that there is a monolithic group of people who use drugs that are causing crime is not helpful and that reducing crime requires that people who are in the criminal justice system are successfully reintegrated with society.

“We need to have a community that is open to the idea of change and redemption and welcoming people back in,” she said. “We want people to join back into the community. We want people to be healthy and happy neighbors. We can’t hold an ‘us versus them’ attitude.”