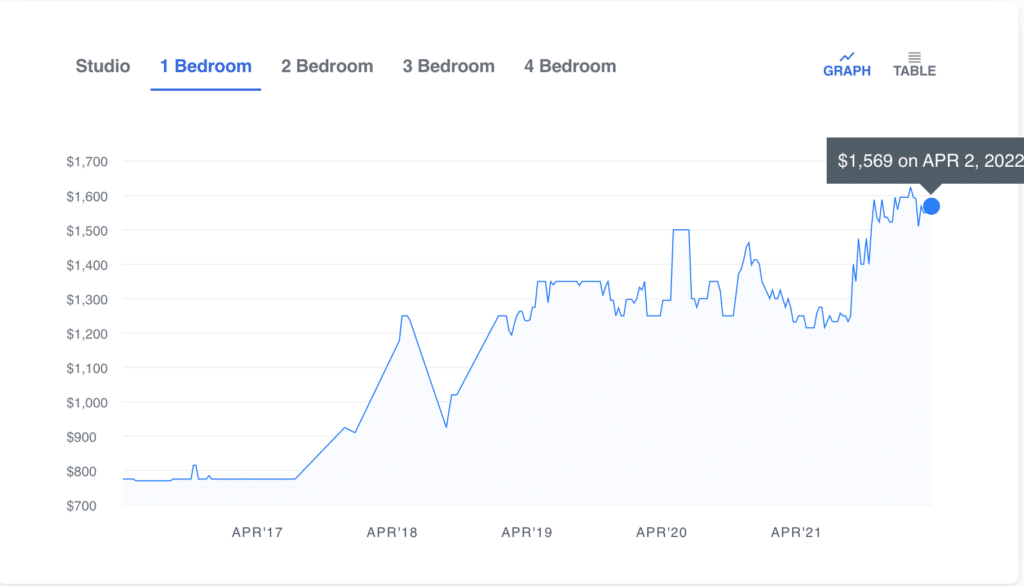

Average rental prices in Nanaimo have soared by another 30 per cent in the last year, according to Zumper, a site that aggregates hundreds of thousands of current rental listings.

Overall, this means that the average rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Nanaimo has more than doubled from what it was just six years ago — from an average of $975 to its current average of $1,990.

Vancouver and Victoria are facing a similar situation, with average market rents rising by 20 per cent in the last six months, according to data released by National Rental Ranking.

Though Nanaimo’s vacancy rate went up slightly from one per cent to 1.6 per cent in the last year, according to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), it’s still far from the three to four per cent vacancy rate that is considered “healthy.” It’s also only slightly above the vacancy rate of Vancouver (1.2 per cent), which is considered to be the most unaffordable city in North America.

The latest State of the Nanaimo Economy report attributes recent rental rate increases and low vacancy rate in part to increased migration and the return of students, which “grew rental demand faster than supply.”

According to the most recent data from Statistics Canada, in the last year more than 100,000 people moved to B.C. Between 2016 and 2021, 89,000 people moved to Vancouver Island. Nanaimo was one of the regions with highest population growth — an increase of 10,523 people from 2016 to 2021.

What does this mean for the average person trying to get by?

Many rental affordability advocates, and various levels of government, use a benchmark that the cost of housing shouldn’t exceed 25 to 30 per cent of a household’s pre-tax income.

A single parent in Nanaimo who works full time at the minimum wage of $15.20 per hour will earn around $31,500 per year before taxes. Using the two-bedroom rental average of $1,990 per month, their rent works out to about $23,880 per year.

However, using the 30 per cent affordability standard means this parent’s rent should technically only be $787.50 per month if they are to avoid what the CMHC describes as being a household in “core need.” This means they’re paying $14,430 more per year than what would be considered affordable.

Put differently, in order to afford a two-bedroom place at current rents, this single parent would have to work about 440 hours per month (or 110 hours per week) to keep monthly rent at 30 per cent of their income.

A single person living on disability income in Nanaimo will receive about $1,358 a month, which includes a maximum shelter allowance of $375 per month, bringing their annual income to about $16,296.

Using the one-bedroom rental average of $1,569 per month in Nanaimo shown on Zumper, they’re likely paying about $18,828 on rent per year. That’s more than their annual income.

However, using the 30 per cent affordability standard, this person should technically be paying $4,888 per year in rent so they also have money outside of housing expenditures for the necessities of life.

Examples like these are echoed in the Canadian Rental Housing Index (CRHI), which finds that the lowest income group of Nanaimo renters spend approximately 72 per cent of their income on rent (versus the highest income group, which spend only an average of 16 per cent).

As rental prices continued to rise (the CRHI use data from 2016), the City of Nanaimo conducted their own renter and landlord survey to get a more accurate picture. The results, which were released in July 2021, show that 79 per cent of respondents report spending more than the benchmark 30 per cent of their income on rent and 28 per cent say they spend more than 50 per cent of their income on rent.

When it came to finding housing, 76 per cent said they struggled to find rentals, citing cost and lack of availability as top reasons.

Why the rental numbers matter

It’s been just over a year since we at The Discourse launched our Making Rent solutions series with an initial feature that sought to lay out the facts of what, exactly, was happening with the rental situation in Nanaimo.

Related: Barely making rent? You’re not alone.

One of the first places I sought information on local rent prices was with the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), who release a yearly rental report on housing trends for major centres across Canada.

However when it came to rental prices in Nanaimo their estimates struck me as low, and their averages weren’t matching what I could easily find in online listings.

According to CMHC data, rents in Nanaimo only went up by seven per cent since last year. So why the discrepancy with the numbers we sourced from current listings?

“So first of all it’s only looking at the average of all renters — so people who live in their current homes. But not people who are looking for new homes,” said Marc Lee, a senior economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, when we spoke to him last year. This tends to skew the numbers downwards, because “there’s still going to be tons of people who have lived in their place for five years or 10 years and are paying much lower rents.”

This was one of the crucial factors for housing affordability — it’s not just that rents are going up in Nanaimo, but also the speed at which they’re rising.

When we looked at current listings from Zumper, which calculates median rents from current listings, it painted a different picture.

From 2016 to 2021 — in just under five years — the average rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Nanaimo had risen by 59 per cent.

What can be done about the rental crisis?

When we spoke to various experts for our solutions-focused series, one thing that came up repeatedly was vacancy control. It’s a type of rent control that stays tied to the unit, so rents can’t be drastically hiked between tenants but rather — like other rent controls — remains linked to the rate of inflation.

Related: How can we make rent more affordable?

Another solution, though not as immediate, is to drastically increase the non-market housing stock. For example municipal, non-profit or government-owned rentals that have subsidized or lower rents geared to income.

Sustainable urban design experts like Patrick Condon believe this not only addresses the issue directly but also indirectly provides strong competition to market-based rentals, which then also helps lower their rents.

Though many municipalities are stuck waiting on provincial and federal funding, experts believe there are some tools that can be leveraged to help the situation. For example, cities can rezone areas as rental-only, as Condon advocates, or require that any development seeking new density for rezoning is required to include 50 per cent affordable housing units.

A new report out this month from the University of Toronto also emphasized the role that local governments can play in meeting housing needs, and cited Victoria and Langford’s 10-year tax exemption for non-profit housing projects as an example.

What are various levels of government doing about it?

Recently, the federal budget unveiled a number of proposals aimed at tackling housing issues, including a two-year ban on non-resident buyers of residential real estate (who make up around two to three percent of homeowners). The budget also promises a new tax-free savings account for first-time buyers, and funding over two years toward both affordable housing acquisition and construction and co-op housing.

However the majority of people struggling to make rent will likely not see any direct benefit from the 2022 federal budget. In an analysis of federal funding on housing affordability between 2017 and 2021, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives found that definitions and targets for affordability tend to serve middle class income earners and incentivize market-rate rental housing.

Last year, the province proposed measures aimed at cooling off real estate transactions, as well new rules around the renoviction of tenants, though the latter was criticized for its weakness and accused of skirting around the implementation of direct measures like vacancy control.

In B.C.’s 2022 budget, most funding continues to go toward housing for the estimated 23,000 people in the province experiencing homelessness. A previously promised renter’s rebate has been directed to people most at risk. The vast majority of applicants seeking funds to support non-profit housing projects last year through the Community Housing Fund were rejected due to budgetary constraints, including a project on Gabriola Island.

Following the lead of other municipalities, Nanaimo now regulates short-term rentals to ensure they are operated by local residents who also live there. The city has also created some incentives for affordable housing using density bonuses, though critics say these incentives are too soft. The city is also exploring options to allow permanent accommodation in RVs as well as updates to its land acquisition policy in support of low-income housing.

For more updates and practical information on renting in Nanaimo, check out The Discourse’s new free resource guide. [end]

Editor’s Note, May 12 , 2022: This is a corrected article. A previous version of the article stated the shelter allowance for people living on disability supplements is an additional payment, it is however included in the monthly $1,358 rate for a single person.