This story is part three of our series on rent in Nanaimo, Making Rent.

Read part one to learn about Nanaimo’s rental and income data.

Read part two to understand how rental rates got so out of control.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter for the latest updates on this reporting.

“In 2015, I rented a one bedroom basement suite for $810 a month including all bills. That’s impossible to find now.”

“Currently been told by our landlord that she wants to move back in so now at eight months pregnant my husband and I are looking for somewhere else to rent. Now it has become harder for us to find a place due to having a very young baby, nobody wants us in their suites because babies cry.”

“I haven’t been able to save any money due to being paycheque to paycheque because of rental costs. I’m at the top of what I am able to pay and am nervous for the next year ahead.”

“You will always just be scraping by, you never get ahead. It just ensures you keep poor people poor by exploiting the only market they have to shelter themselves and their families. Lower rent costs, we don’t need ‘affordable housing’ elegiacally built. All fucking housing should be affordable, it’s a NECESSITY.

“Finding a decent affordable place to live that has at least one bedroom and one bathroom that I can afford on my pension and my very part-time work now. I currently live in a 500 square foot single car garage converted. It’s affordable but it’s so small I can not even have company over for dinner.”

“There’s so little available and what is available is super expensive. I stayed in my earlier bad situation for much longer than I wanted to just because there weren’t any other affordable choices for me.”

These are just some of the responses out of more than a hundred we received from Nanaimo residents to our renter’s survey that informed this series on rental affordability, Making Rent.

In parts one and two of this series, we looked at the shortage of rentals here, how rates have skyrocketed in recent years at a rate much faster than wages, and why it got this way.

But what can be done about it? Here’s what experts are advocating for and what’s currently on the table in Nanaimo.

How can drastic rent hikes and illegal renovictions be prevented?

Many experts we heard from, like Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives economist Marc Lee, advocate for the immediate re-introduction of regulatory interventions like vacancy control – a type of rent control that is tied to the rental unit rather than the tenant – which B.C. had from 1974 to 1983. It’s aim is to keep rent raises aligned with the rate of inflation and to prevent rent from being drastically raised between tenancies, which can incentivize evictions.

Lee also believes it would remove the incentive for real estate investment trusts to then “sweep in and buy up buildings on the cheap and then clear people out.”

Real estate investment trusts, or REITs, are companies that purchase or develop and manage real estate assets like rental buildings to generate a profit for investors, and some residents in Nanaimo have noticed that bigger REITs like Toronto-based Starlight Investments are increasingly visible in their previously affordable neighbourhoods.

The province recently took a step in the direction of vacancy control on March 1 when housing minister David Eby proposed legislative changes that included extending the existing rent freeze to the end of 2021, continuing to tie future rent increases to inflation and imposing new rules on landlords seeking to renovict tenants that require them to prove the changes are substantial enough to require them to vacate the unit.

Advocates like the Vancouver Tenants’ Union say these new measures don’t go far enough to protect tenants from renovictions, and that no landlord should be able to evict a tenant permanently for the purpose of temporarily renovating their unit. Meanwhile advocates like LandlordBC say it creates a disincentive to invest in aging rental stock.

The proposed legislative changes passed on March 8.

What about non-market housing?

The next step recommended by experts is to dramatically increase the production of non-market housing, says Patrick Condon, a sustainable urban design expert and the James Taylor Chair in Landscape and Liveable Environments at the University of British Columbia. He defines non-market housing as any housing protected from market forces, thus offering affordable rents or ownership in perpetuity.

“It’s a way to pull housing off the vagaries of the international housing market, which is destroying us at the moment,” says Condon, who notes that in places like Vienna, Austria, about 60 per cent of the housing stock is either owned by the municipal government or by state-subsidized non-profits.

The existence of a very large non-market housing sector has the added effect of lowering the cost of market-level condos and rental units, he adds, because of the strong cost competition with the non-market sector.

The City of Nanaimo defines non-market housing as that which is provided at income assistance levels and/or on a rent-geared-to-income basis of 30 per cent of a household’s income, says Nanaimo’s social planner David Stewart.

Using this definition, approximately four per cent of the city’s housing stock can be considered non-market rentals, based on a recently completed inventory of affordable and supportive housing done as part of the city’s Health and Housing Task Force and the 2016 Census.

Many people don’t realize that Vancouver, which is often seen as the poster child for unaffordable housing, actually has many thousands more units of non-market housing, says Condon, about 12 per cent of a total of roughly 300,000 housing units.

“So that’s a lot,” he says. Some of this is social housing but many are co-operative units built in the 1970s and ‘80s on the municipal, provincial and federal level that were considered middle-class housing. Housing co-ops are generally non-profit, and collectively owned and operated by the people who live there. (There are no co-operative housing units in Nanaimo).

By the ’90s, “when everybody’s faith in the market as ‘the solution to all problems’ became exaggerated,” the government had stepped back from their role of providing affordable housing, says Condon.

Former Prime Ministers Brian Mulroney and Jean Chrétien continued to keep the federal government out of the housing market, and provinces followed suit, he says, to the point where they mostly focused on supplying housing for the most disadvantaged and vulnerable.

This has led to what he calls the “missing middle”: that the middle class have been left to fend for themselves, which only further hurts the economy, he says. Young to middle-aged working people are the primary contributors to the economy and tax base, he adds, but struggle to do so if most of their income is spent on housing.

Now the government is playing catch up, says Chris Beaton, executive director of the Nanaimo Aboriginal Centre, which operates affordable housing, among other initiatives.

“When you look at what’s happening in the province right now, or on Vancouver Island, BC Housing is spending a lot of money on buying hotels, or trying to replace tent cities, as it should. But that’s taking up capital dollars,” he says.

“Every time you spend a dollar somewhere, you’re taking away from another potential. So when you say, ‘Well, we could build 500 units at these rent levels…or we can build 200 and make them really affordable, which one should we do?’ It’s a challenge. It’s not an easy decision. But I’m not sure that we’re doing our best in making sure that the units truly are affordable.”

What does industry say about it?

A stronger government role is definitely needed in building affordable housing, agrees Michael Brooks, CEO of the Real Property Association of Canada, but he disagrees with interventions like vacancy control, which he thinks will only exacerbate the problem by driving away investment and therefore new rental supply.

“Economics 101: the market sets the apartment rental rate. If you have adequate supply, there’s no pricing power in the landlord. If you have attracted capital to Nanaimo, and there’s enough new apartments being built, whether they’re new buildings or basement apartments being available because the return is good. If you make it an attractive environment for capital, you will have supply balance,” he says. “And if you have supply balance, there’s no pricing power of a landlord to hike rents because that tenant can go across the street and pay less money.”

He also says it’s folly to expect the private sector to fix the problem of affordable rentals, though he is in favour of municipalities striking deals with developers to make a percentage of their developments affordable or below-market in exchange for things like inclusionary zoning or allowances for higher density.

“What’s the role of the private sector? Is it the job of the private sector to provide the low-market-rate housing? It’s very difficult to do that unless you cut corners,” he says. “That’s the job of governments and NGOs, to get together to figure out, ‘how do we provide below-market-rate housing?’”

How can the city help with the rental affordability crisis?

On a local level, there is some movement towards increasing the non-market housing stock.

“There’s been huge investments in affordable housing [lately], but when you go for decades without a huge amount of housing and then you have so many factors compounding things, it makes it hard to keep up,” says Laura McLeod, communications specialist at BC Housing, who have partnered with the City of Nanaimo to build a mix of units in Nanaimo, some of which are aimed at addressing what Condon referred to as the “missing middle.”

These are the units that are offered at ‘affordable market rent’, that is slightly below-market, says McLeod. “And then a certain percentage of the housing is rent geared to income, so that is when your rent is 30 per cent of your gross monthly income, and then a certain percentage of those builds are shelter-rate housing, so that’s currently $375 a month.”

Though housing is the responsibility of the province, municipalities have an important role to play in putting provincial funds to use by contributing land, development permits, zoning changes and various waivers in taxes and fees.

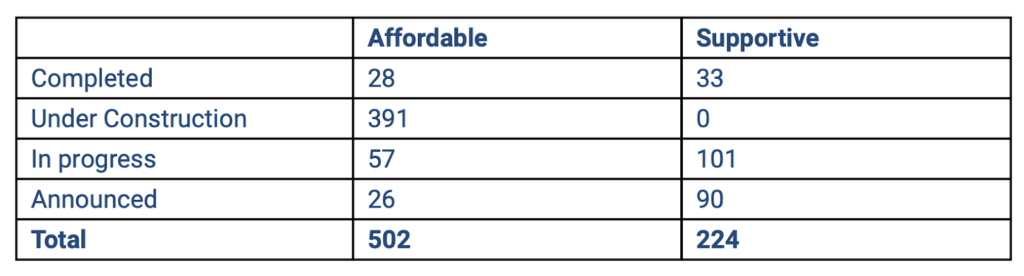

Nanaimo’s Affordable Housing Strategy, adopted in 2018, aims to add 200 to 240 supportive housing units, 100 to 120 rental supplements and 400 to 600 units that rent at 60 to 90 per cent below market, within three to five years. Of these, according to the numbers provided from the city, 61 have been completed so far, with 391 under construction.

Another tool that municipalities can utilize is the power to rezone whole areas of the city as rental-only, which happened when the province changed the municipal act in 2018 to allow cities to zone not just by use but by tenure type.

“The whole point of a rental-only zoning authority is so rental-type projects can compete when they want to buy land for that purpose,” says Condon, who adds that it’s also a way of protecting existing rental stock. “Otherwise, they get out-competed by the condominium developers. So it’s, it’s a way of managing land price.”

It’s a contentious issue because developers and building owners argue that it lowers the value of their holdings. But “that’s the whole point,” says Condon. “It’s not the building that’s costing too much for people to buy or to rent, because the cost of building a square foot of a building hasn’t gone up substantially in the last 30 or 40 years. What has gone up is the purchase price of land.”

Is rental zoning something that would work in Nanaimo?

“At the time [it went through] I thought, ‘Oh that’s a really innovative idea,’ but I don’t think it’s required in Nanaimo, to be honest,” says city councillor Tyler Brown. “Because we have so much rental being built by private industry or B.C. Housing. This was in my campaign platform as something we should look at but when I saw the building permit stats for 2018 there’s a drastic response from private industry to build rental-only.”

But that doesn’t mean these new rental units are affordable. As part of its housing strategy, the city said it will explore additional ways to incentivize developers to build affordable units through tax exemptions or density bonuses, a move which Brooks agrees with.

For example, the city can demand that any new density approved for rezoning is split between 50 per cent private and 50 per cent affordable housing for the public, says Paul Finch, who is responsible for the British Columbia Government and Service Employees’ Union’s policy on housing affordability and land economics.

It’s also important to be wary of how zoning changes given out by municipalities can actually vastly increase the value of private land for developers, he says.

“If you increase the zoning, it’s basically like giving away money,” Finch says. Over the last decade, municipalities have been giving away zoning “like candy” to developers without having any requirements for affordability, he explains, despite the fact that the value of land is also greatly increased by its proximity to publicly-funded services like transit systems and parks.

In Nanaimo, there are currently no density bonuses specifically awarded for affordable rental units, though non-profit housing projects are offered development cost charge reductions, which are fees charged by the city to cover infrastructure costs like water and roads, among other incentives.

Stewart says city staff are expected to propose changes to the city’s bylaws related to density bonuses for affordable housing this spring.

What about short-term rentals and infill housing in Nanaimo?

The City of Nanaimo is also reviewing legislation to limit short-term rentals like AirBnBs and their impacts on the availability of long term rental housing. According to the city, in October 2020 there were 501 active AirBnB and VRBO rentals in Nanaimo, 67 per cent of which were for the entire home. Changes now in effect require owners operating short-term rentals to carry a business license.

In addition, the city is looking at ways to support more infill rental housing, like secondary rental suites in the form of coach houses. In 2018, just 18 new secondary suites were issued permits, according to the city’s most recent housing strategy update.

Modular forms of infill housing like tiny houses are not currently permitted as secondary suites. Stewart says to expect updates on this policy mid-April when the city releases its annual affordable housing strategy update.

At the end of the day, it remains to be seen what measures the city can take and what effect it will have, says councillor Brown.“I think that the housing market in general is clearly complex, and I don’t think there’s one silver bullet that is sitting there for renters or homeowners about how we might do something about it,” says Brown. “It needs to be a comprehensive policy approach to fixing it.” [end]

This is part three in our series on rental affordability in Nanaimo, Making Rent. This original reporting is made possible by the monthly members who support this work.