A massive diversion on the Quw’utsun Sta’lo (Cowichan River) has led to multiple search and rescue groups in the region urging recreationalists — specifically tubers — to stay away from the section of river that stretches from Little Beach to Skutz Falls. But a local river steward says that while the conditions aren’t favourable for humans, this could be great news for the fish that call the river home and face a few critical weeks ahead as water levels in Cowichan Lake — which feeds into the river — hit unexpected lows.

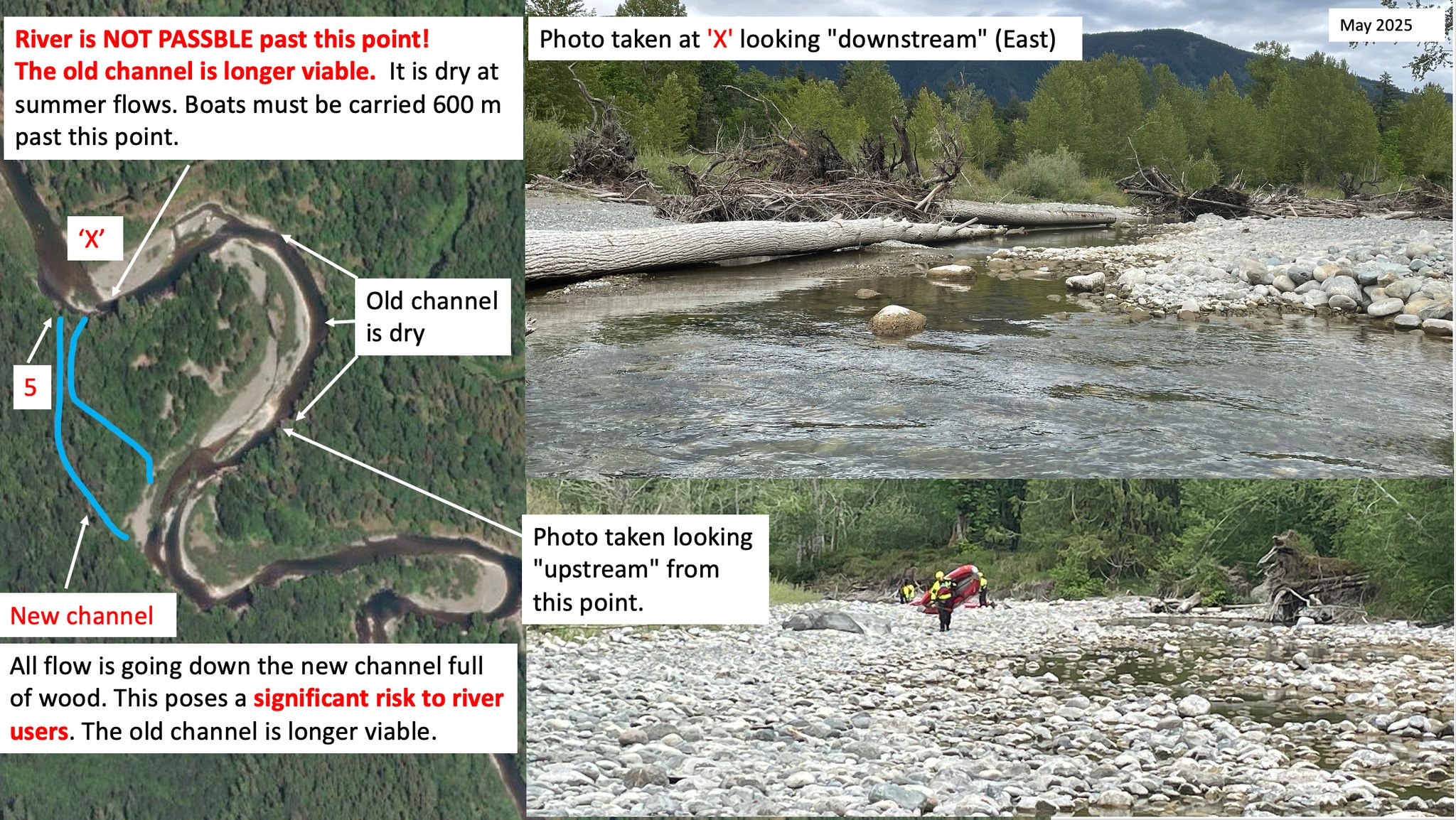

Earlier this month, Ladysmith Search and Rescue (SAR) posted a map on social media showing that the Quw’utsun Sta’lo diverted from its typical path, flowing in a new channel directly through the surrounding forest. The main flow of the river now goes through log jams, making it impassable between Little Beach and Skutz Falls.

Jeff Lewis, a Swiftwater Safety Rescue team leader with Ladysmith SAR, said the rescue team is concerned about out-of-towners and inexperienced river users who may visit during the summer months and be caught off guard by the diversion.

“This is essentially a death trap for anyone that flows directly into it,” Lewis said, pointing out that the hazards such as fallen trees and other wood debris aren’t visible from upstream and would likely catch anyone floating in a tube by surprise.

Meanwhile, Joe Saysell, a fishing guide and long-time advocate for the river, said the new diversion will be an overall positive development for the fish, which are facing increasing pressures due to climate change and its impacts on the environment.

“All that woody debris is good, it creates nice cover for [the fish],” he said.

A new hazard for Cowichan River users

Lewis told The Discourse that high river flows in winter 2023 broke through a bend in the river, splitting the flow and opening up the new channel through the forest. That, combined with low water levels this year, has led to the original path of the river drying up and the new channel becoming the dominant path.

A common pullout site for tubers is a stretch of shore known as Little Beach, located not far downstream from the town of Lake Cowichan where tubers typically enter the river. Every year, search and rescue crews are called to the stretch of river just past Little Beach to rescue tubers who either miss the pullout or think they can float the roughly 15 kilometres to the next pullout, Lewis said.

Saysell said BC Parks has printed signs and placed them at Skutz Falls and Stoltz Pool in Cowichan River Park. He said he spoke with the Cowichan Valley Regional District about putting those same signs up at Little Beach and plans to put the copies he was given by BC Parks up around Lake Cowichan to warn tubers of the hazards on the river.

“Cowichan River, from Lake Cowichan to Skutz Falls, is impassable due to log jams and multiple blockages,” the BC Parks sign reads.

Lewis said the new channel will most likely remain a hazard for several years and that it would take a few winters of high water flow to clear out the debris.

“We just really want to emphasize to people that this year is different. This is a truly life-threatening new hazard.”

A race to save fry

Woody debris in the new channel provides the fish with a place to hide from predators, such as heron, and stay cool in the summer months, Saysell said. Since the river flows through woodland, Saysell expects the fish will have plenty to eat. Additionally, the physical barrier the diversion creates will result in fewer people fishing in the area, thereby taking pressure off the fish.

The challenge, Saysell said, is getting the fish that are trapped in small pools on the dried-up section of the river over to the new channel, almost 500 metres away.

When The Discourse spoke with Saysell, he had just finished a day of hauling fry out of the pools that were at risk of drying up and moving them to the new channel. He estimated that 15,000 juvenile fish, ranging from steelhead trout to coho and Chinook salmon, had been saved so far, but said it was a critical time to rescue the trapped fry as the conditions could change drastically from day to day.

“If you wait another two days, certain pools will dry up and be gone. So we got all the real critical ones, and then, sure enough, two days later, they were bone dry. It was good to get everything out of there,” Saysell said.

According to Saysell, the vast majority of fry are out of the dried-up section of the river, and now he and others rescuing the fish will pick away at the remaining pools over the coming weeks.

However, it’s not lost on Saysell that the new stretch of river is close to where, two years ago, a massive die-off of fish occurred, resulting in an estimated 84,000 fish being killed.

While the new channel and woody debris in it could be good news for fry seeking cool spots to rest and feed, Saysell said the coming weeks will be a preview of how river conditions will play out this summer.

“Unless we get lucky and get a hard June rain, we could be in huge trouble this summer and make that fish kill of two years ago look like nothing.”

Impacts of climate change on the river

Saysell’s deadline to rescue the remaining fish in the dried up portion of the river is June 15, which is when he expects the remaining pools to go dry. But he said water levels are already low in the river and the way it dried up, along with the dryer spring weather, is unprecedented.

“Maybe I don’t even have that long to get them out,” he said.

Saysell said the river is dealing with the double-whammy effects of climate change and second-growth logging, which lead to huge swings in water levels over a short period that the river and surrounding creeks can’t handle.

The loss of trees in the watershed means there is nothing to slow down the water flowing into the lake and river. Instead, it rushes in and carves up the landscape as it does so. An increase in extreme weather conditions due to climate change — such as extreme rainfall events — makes this scenario even worse.

”The creeks that are filling the lake up, they explode. They roar into the lake. They lift the lake and the lake pours into the river,” Saysell said. “It unravels all the banks and rips the trees out and everything else.”

The resulting weakened river banks, which once meandered through the land, are more likely to fall apart as the river naturally finds the straightest path to the ocean.

“When I grew up here it would rain and the river would go up slowly. Today, it’s up and down, up and down, up and down — like a yo-yo,” he said.

Earlier in May, it was reported that water levels in Cowichan Lake were much lower than they were at the same time last year.

Saysell told The Discourse that over two weeks, from April 20 to May 2, water levels in the lake went from 110 per cent to 68 per cent. He said as someone who has been living and fishing on the river, this is something he had never seen in his entire life.