Editor’s note, July 18, 2025: The section on the RCMP altercation with Curtis in this story has been modified to clarify that police did not state what weapons were observed in the area at the time. A section of the Criminal Code defining weapons has been added, as well as research regarding harm caused by police against people who are unhoused and use substances. The response from North Cowichan Cop Watch has also been clarified to better represent their criticism of the police response to both Curtis and The Discourse’s questions.

In early June, Cowichan Valley community members came together to build a shelter for Curtis, an unhoused senior and “Indian Day School” survivor living on the streets of Duncan and North Cowichan (who The Discourse has chosen to identify by first name only to protect his wellbeing). The shelter was made of wood and attached to wheels so it could be portable and move around.

After a week of use, Curtis lost his shelter following an altercation with law enforcement that turned physical and led to his displacement again. Now, community members are raising concerns about how sheltering bylaws are being communicated and enforced in Duncan and North Cowichan.

Local advocacy group North Cowichan Cop Watch said bylaws, and the officers that enforce them, need to be clearer about where people can shelter and what types of shelters are permitted in parks. The group adds that the rules must be clearly communicated to the individuals who are being moved from Lewis Street — where a community of unhoused people reside near Warmland House shelter — as the current lack of clarity can lead to misunderstandings and violence against unhoused people, especially when incidents cross jurisdictional lines.

Because of the nature of North Cowichan Cop Watch’s work and concerns for members’ safety, the Discourse has chosen not to name specific individuals in the group and is attributing statements to the group as a whole.

“Many people on Lewis Street are shaken and saddened by the violence they witnessed directed at a well known and respected Elder, but they also have seen many incidents like this,” North Cowichan Cop Watch said in a statement.

North Cowichan chief administrative officer Ted Swabey said the current housing crisis and lack of support options for people experiencing homelessness “underscores the urgent need for increased investment in social infrastructure by our provincial and federal partners” and the municipality will continue to advocate for those resources.

John Horn, North Cowichan’s director of social planning and protective services, said the municipality will work to ensure its bylaws are properly communicated to those who need a place to shelter. He said the municipality is also determining exactly where people can shelter within the current bylaw to make a map that includes examples of permissible shelters.

“There’s a fine distinction between sheltering and setting up an encampment in a park but that can get lost sometimes in the dialogue,” he said.

Meanwhile, the City of Duncan’s bylaw supervisor Mike Dunn pointed to a page on the city’s website outlining sheltering rules. He said the city has exceeded what is required by the province in communicating sheltering bylaws for unhoused people.

Curtis said the altercation and lack of clarity on where he could take his shelter left him feeling “ripped off.”

“I thought that they just made a big joke out of me,” he said. “I just want people to get along and help each other and build them up. Don’t tear them down.”

Altercation prompts criticism from local group

Curtis, who is originally from Ladysmith, had been sleeping directly on the sidewalk on Lewis Street for months, including through the winter.

On June 3, peers living on Lewis Street chose Curtis to receive the first portable wooden shelter built by North Cowichan Cop Watch and community members. He used it for close to one week before North Cowichan bylaw officers asked him to move because he was violating the municipality’s Parks and Public Places Regulation bylaw in the 2500 block of Lewis Street, according to Swabey.

North Cowichan bylaw requested RCMP assistance in removing Curtis, who was allegedly refusing directions from bylaw officers, from his shelter. Curtis told The Discourse he believed he didn’t need to move because others living around him in tents were not being asked to move along.

According to RCMP Staff Sgt. Kris Clark, the responding RCMP officer said they observed several weapons in the area while attempting to de-escalate the situation and ultimately made the decision to arrest Curtis, but did not clarify what the weapons were.

“Upon doing so they were physically surrounded by bystanders. Due to the perceived level of risk to officer safety, the officer disengaged and requested backup,” Clark said.

When asked for clarification on what weapons the officer saw in the area, RCMP spokesperson Cpl. Alex Berube said there is no more information to publicly share. The Criminal Code in Canada uses a very broad definition of what a weapon could be. It says it is “anything used, designed to be used or intended for use in causing death and injury to a person or for the purpose of intimidating any person.” This means it can be anything from a firearm to an everyday object and is left up to the interpretation of law enforcement.

The Discourse was not able to receive any more clarity on what the officer identified as a weapon in this instance.

Bystanders reported that around seven RCMP cars responded to the calls for backup, according to North Cowichan Cop Watch, and video and photos from the altercation shown to The Discourse also show a significant police response. North Cowichan Cop Watch noted that by the Criminal Code definition, weapons could be found anywhere in the Cowichan Valley but that people who are unhoused tend to be overpoliced and targeted compared to other community members.

A report by Pivot Legal Society, which has also been shared by B.C.’s Office of the Human Rights Commissioner, found that policing practices in B.C. “directly and indirectly lead to negative health outcomes, opioid-related harms and safety issues” for people living on the street. People across B.C. were surveyed for the report and shared experiences of harassment, displacement and violence at the hands of police and policing institutions, the report says.

The report also finds that behavioural conditions and the court system impact the lives of unhoused people and people who use substances. These behavioural conditions, also referred to as court-imposed rules in the report, include geographic area restrictions, curfews and rules that regulate and prohibit people from carrying things like harm reduction supplies.

“Participants shared how behavioural conditions fail to acknowledge the realities and complexities of the lives of people experiencing homelessness and people who rely on substances,” the report says. “The result is that behavioural conditions — often justified as working in the interest of public safety — endanger the health, safety and dignity of people already living with intersecting barriers, making them less safe and keeping them trapped in cycles of criminalization.”

“At the end of the day, [RCMP] brought cruisers and their own arms and could have easily ended the escalation,” representatives from North Cowichan Cop Watch said in a statement to The Discourse, noting that police could have disengaged peacefully to end the altercation.

North Cowichan Cop Watch said that at the time, Curtis was suffering from injuries from a previous incident where he was hit by a car. He is elderly and disabled and was unable to move out of his shelter fast enough and the group said this led to a violent attempt of removal by police.

The group alleged at least one constable became physical with Curtis and attempted to pull him out of the shelter while another tried to pull his arm through a small gap in the structure resulting in cuts on his arm. North Cowichan Cop Watch said the constable who was most involved in the altercation refused to give his name and badge number when bystanders requested, something they must do when asked.

In response, Clark said “it did not seem safe or appropriate for an officer to give this information until the situation was resolved.”

Police told The Discourse the altercation ended when Curtis agreed to move his shelter.

Cross-jurisdictional confusion

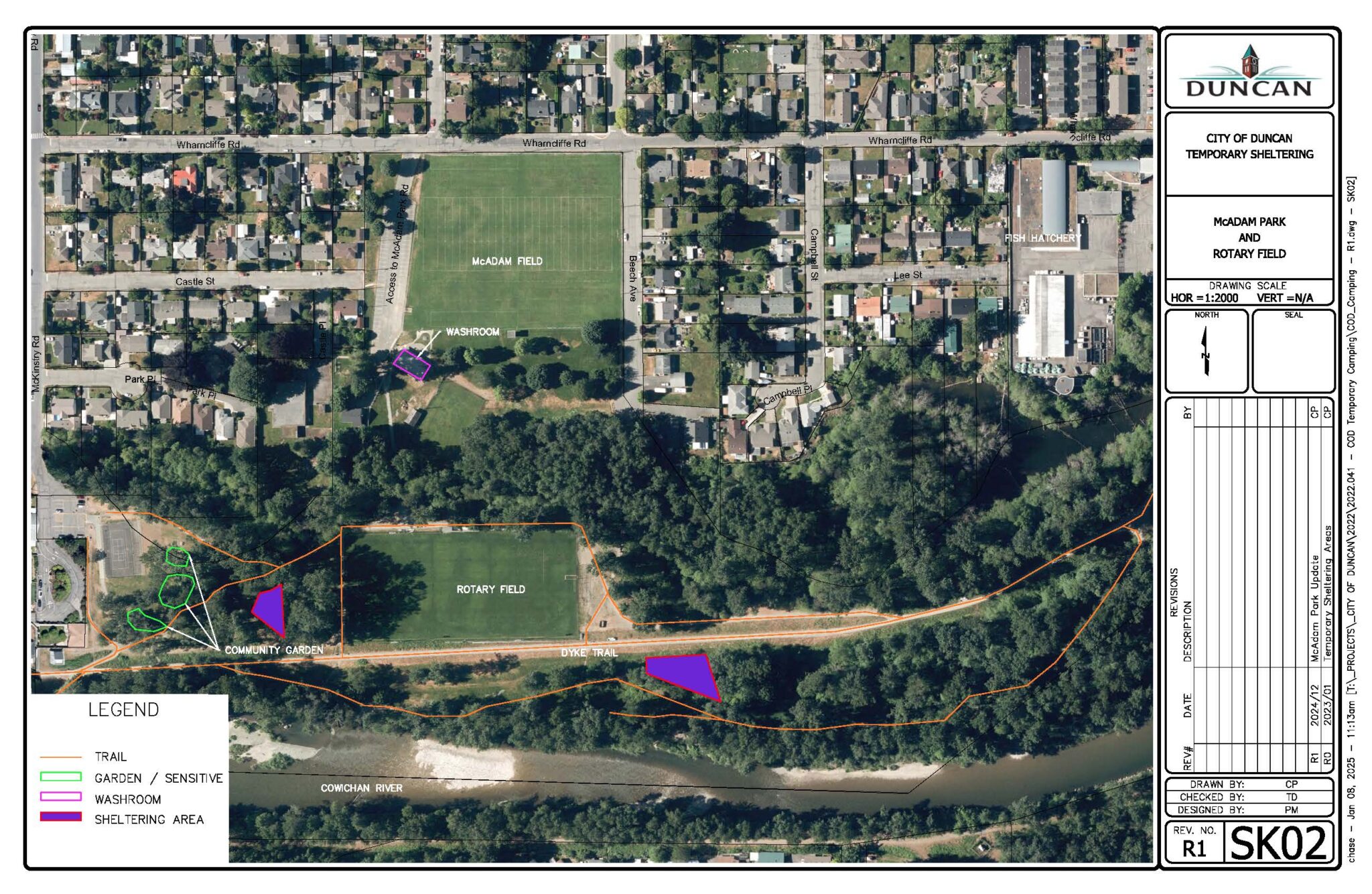

Curtis was then told by North Cowichan bylaw he could take his shelter to Rotary Park in Duncan, according to North Cowichan Cop Watch. However, upon arrival, he was met by Duncan bylaw officers who said a portable shelter of that kind was not permitted in the park and, according to a statement from North Cowichan Cop Watch, were not willing to explain to Curits or other witnesses why the shelter wasn’t allowed.

Duncan Mayor Michelle Staples said North Cowichan staff should have redirected Curtis to somewhere within the municipality, rather than to a park in Duncan. She said it is the responsibility of each jurisdiction to communicate its own policies regarding sheltering and designated locations where people can shelter.

“We understand how confusing and disheartening it can be when individuals are unsure where they are allowed to shelter,” Staples said. “Our staff encourage coordination between jurisdictions that is respectful, consistent and trauma-informed.”

John Horn, North Cowichan’s director of social planning and protective services, said that similar to Duncan, many of the parks in the core of North Cowichan near Lewis Street are not suitable for overnight sheltering due to their small size and proximity to spaces like playgrounds, community gardens or a bandshell.

But even if there was a park that met all the requirements for sheltering, the shelter built for Curtis still wouldn’t have met the definition of a temporary shelter. North Cowichan’s Parks and Public Places Regulation bylaw defines a temporary shelter as a tent, lean-to or other form of shelter constructed from nylon, plastic or cardboard or similar non-rigid material, and explicitly excludes structures with a wood frame.

From the perspective of bylaw officers and the municipality, Curtis’ shelter was deemed too permanent to count as a temporary shelter.

“You are allowed to protect yourself from the elements but you can’t set up an encampment,” Horn said.

Curtis was allowed to stay overnight with his shelter in Rotary Park, but Duncan bylaw officers returned the next day to dismantle it. Curtis’ friends and community members intervened and used a truck to take the shelter and his belongings for safe keeping.

If they had not done so, his belongings and shelter would have been thrown out, according to North Cowichan Cop Watch.

A community solution for shelter in the face of poor alternatives

Community members who don’t live on Lewis Street built the portable shelter that Curtis was using as a possible solution to the lack of shelter options in the area. It is just under a metre wide and almost two metres long, with three walls, a floor and a roof. The wheels, mounted on spinning casters and screwed to the bottom, were included to make the shelter portable if bylaw required it to be moved.

While the shelter is moveable, it is made from materials not permitted under city bylaws, namely plywood.

The prototype shelter that was gifted to Curtis included his name on it in large lettering as well as a phone number to call if any issues arise. The phone number was attached to a community member who could respond in case of emergency.

He hoped the rigid shelter would also help protect him and his belongings as he planned to install a door that could be padlocked when he wasn’t there or sleeping.

North Cowichan Cop Watch said many of the design considerations for the shelter came from community members living on Lewis Street, where options for nearby shelter are limited and they are often asked to pack up and move their belongings on a daily basis. The area is near services such as Island Health’s overdose prevention site, but the closest legal place to shelter outside is Rotary Park in Duncan.

Few people feel safe or able-bodied enough to go to Rotary Park, North Cowichan Cop Watch said, noting the park is dark, isolated and that there are reports of unhoused women being assaulted there.

“Continually, we hear of the ill-suited and dangerous nature of Rotary Park. Furthermore, it is an area with cottonwood trees, which are notorious for dropping branches which have fallen on tents,” the group said in a statement.

North Cowichan Cop Watch called on mayors, councillors and North Cowichan and Duncan municipal staff to designate a “fully serviced encampment site” to meet the needs of the unhoused community.

“There are choices to be made and we need to do better,” the group said.

Horn said there are two models for setting up a full-time encampment in North Cowichan — one that would see unhoused residents scattered across the municipality in many smaller encampments, or one large, managed encampment that is centrally located near services.

Managing a large encampment can demand significant resources to maintain order and safety, according to Horn, but dispersing individuals across multiple sites poses logistical challenges, such as ensuring people have access to services.

“We have to figure out what’s most appropriate for North Cowichan,” he said.

For now, North Cowichan Cop Watch said plans to build more portable shelters like the one given to Curtis are on hold.

Municipalities working to make the rules for overnight sheltering more clear

In B.C., there are no provincial laws that explicitly ban or permit overnight sheltering in parks. Instead, the rules are influenced by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, court rulings and municipal bylaws.

In Victoria (City) v. Adams, the B.C. Court of Appeal found that a City of Victoria bylaw preventing unhoused people from sheltering overnight in city parks violated their Section 7 Charter rights. The ruling established that, in the absence of adequate indoor shelter or housing, people must be allowed to set up temporary structures or tents to shelter outdoors.

As a result, many municipalities amended their parks bylaws to include provisions allowing overnight sheltering for unhoused people. However, they will often rely on other bylaws, such as those prohibiting obstruction of streets sidewalks, loitering or panhandling to evict or displace people sheltering outside.

In Duncan and North Cowichan, rather than banning sheltering in specific parks, the bylaws define where temporary shelters are not allowed — for example, within 40 metres of a playground, community garden or within 10 metres of a sidewalk.

In both jurisdictions, this limits the available spots where people can shelter overnight, as many of the parks in the core areas of Duncan North Cowichan are small and include features such as community gardens, waterparks and sports fields, which restrict where shelters can be placed.

Mike Dunn, the City of Duncan’s bylaw supervisor, said the city created a webpage outlining temporary overnight sheltering rules to help reduce confusion. The page also notes that Rotary Park is one of the few locations where overnight sheltering is allowed and won’t violate any of the distance rules.

Making the webpage was a step “above and beyond” what was required by the court ruling, Dunn said. But advocates from North Cowichan Cop Watch disagree.

“Saying that communicating directly with community members is going ‘above and beyond’ is absolutely absurd,” said North Cowichan Cop Watch in a statement to The Discourse. “There was shown to be a complete gap in communication between the bylaw departments of North Cowichan and Duncan about sheltering and an utter disinterest in rectifying the situation despite dire consequences.”

At the time of writing, The Discourse found that the City of Duncan parks bylaw specifically defines a temporary shelter as a “tent, lean-to or other form of shelter that is temporary and portable, constructed from nylon, plastic, cardboard or other similar non-rigid material … and does not include wood frame or portable structures.”

However, the webpage that Dunn pointed to only states that an “overnight shelter must be temporary (for example tents or shelter constructed from a tarp, plastic or cardboard),” with no mention of wood shelters.

When asked how someone without internet access — a reality for many people who are unhoused — might learn about the bylaw rules, Dunn told The Discourse bylaw officers carry paper copies of the relevant sections in their vehicles. This means people who are unhoused and sheltering outdoors may need to ask bylaw officers for the paper copies. But in many cases, people living on the streets are hesitant to communicate with law enforcement due to negative encounters between the two groups.

One way the city clarifies its sheltering bylaws is by installing signs at Rotary Park to notify park users and those seeking shelter about the rules, according to Dunn.

Rachel Hastings, manager of building and bylaw services with the City of Duncan, said she attends collaborative meetings to share this type of information with outreach teams, including the Cowichan Community Action Team, which employs a peer coordinator.

The information is also included in the Cowichan Street Survival Guide, a widely utilized resource distributed by the Community Action Team and Our Cowichan Communities Health Network.

The City of Victoria created a printable handout that explains the rules for sheltering in parks overnight in easy-to-understand language, including the definition of a shelter and where and when they can be put up. The paper copies of the bylaw that Duncan bylaw officers carry do not include the definition of a temporary shelter.

“It does provide a lot of information,” Hastings said when asked about the City of Victoria’s handout. “I agree that the sheet that we have does not include the definition of a temporary shelter or a map. The definition can certainly be added to help clarify what is permitted to be erected.”

Following the altercation with Curtis and questions from The Discourse and local advocates, Horn told The Discourse that North Cowichan plans to create a printable handout map of its entire park system. The handout would identify where sheltering is allowed as well as educate people about the types of shelters that are permitted.

“We’re going to give it to folks, and we’re going to say ‘The green dots, you can go to, the red dots you can’t, and this is where you can go to shelter,’” Horn said. “It will be really clear about what sheltering looks like versus setting up a home in a park.”

Work is already underway to survey parks in the municipality to determine if they are suitable for sheltering under the current bylaw. Horn said they plan to get the map into people’s hands this summer.

Intervention from senior levels of government needed for more shelter space

North Cowichan and the City of Duncan don’t have direct control over public housing or social services, such as shelters, but can advocate to senior levels of government for support.

“The city continues to advocate alongside our local government partners and service providers for year-round, adequately resourced shelter and housing solutions. We are specifically asking the province to build more housing sites like The Village at 610 Trunk Rd.,” Staples said.

Horn said he hopes North Cowichan will be successful in securing an overnight shelter this winter that would operate seven days a week. By 2026, the goal is to have a shelter that operates full time in the winter.

Ultimately, the long-term vision is a year-round, 24-hour facility, Horn said, though operating costs are estimated at around $1 million annually. In the short term, the municipality’s priority is finding a location for an overnight winter shelter in order to secure funding from the province.

“If we have the right place and we’ve got the support of the community and support of all the jurisdictions, it’s a reasonable ask for the community. At least we can provide shelter to folks, if not housing,” he said.