A precedent-setting, first-of-its kind agreement between Cowichan Tribes First Nation and the Province of B.C. will reimagine the way land and water is protected in the province, starting with the Xwulqw’selu (Koksilah) watershed.

For the past three years, Cowichan Tribes and the province have been working towards signing the Xwulqw’selu Watershed Planning Agreement and did so on Friday, May 12 at the Quw’utsun Cultural Centre, located on Quw’utsun lands.

The signing marks the beginning of a process that will result in a long-term plan to steward the Xwulqw’selu watershed and ensure it is healthy for generations to come. A water sustainability plan is one of few legal tools that could fundamentally change how resources are managed, including on private lands.

The process will be jointly led by Cowichan Tribes and the province and will honour the inextinguishable rights of the Quw’utsun people and their relationship to the land that has been present for millennia and is ongoing.

“This agreement is a commitment to take those next steps together,” said Cowichan Tribes Chief Lydia Hwitsum at the signing ceremony in May. “It’s going to take a lot more helping hands and hearts to get this work done … It’s our commitment to the watershed and to find a path forward to address the challenging issues we’re facing around water: Drought, floods, water quality, impacts on our fish and our community and the impact on the exercise of our rights.”

The Xwulqw’selu Sta’lo’ is in need

“This watershed is integral to the identity of our nation and our ongoing relationship with these lands and waters we call home,” said Larry George, the director of Lulumexun Lands and Self-Governance with Cowichan Tribes, at an information night in May.

The Xwulqw’selu Sta’lo’ (Koksilah River) and its watershed are central to Quw’utsun creation stories and carry cultural and spiritual significance. Hwsalu-utsum, a multi-summit ridge in the watershed, is where the first man, Syalutsa, fell from the sky. Several tributaries that flow into the river originate from Hwsalu-utsum and the watershed itself carries many more sacred places and stories for the Quw’utsun People.

“Stories of our first peoples continue to inform who we are as Quw’utsun Hwulmuhw Mustimuhw (Cowichan Peoples),” George said. “Upholding the teachings passed on from our ancestors, such as Syalutsa, has sustained our relationship with our territory since time immemorial.”

The watershed has also served as a place of significance for fishing, harvesting and hunting for millennia. Many different types of wildlife call the Xwulqw’selu watershed home. Fish such as chinook, coho and chum salmon, as well as steelhead and resident trout, make their way through the waters alongside other wildlife like birds, mammals and amphibians. Culturally and ecologically significant plant and tree species can also be found throughout the watershed such as xpey’ (western redcedar), salal, ocean spray, salmonberry, swordfern, maidenhair fern and more.

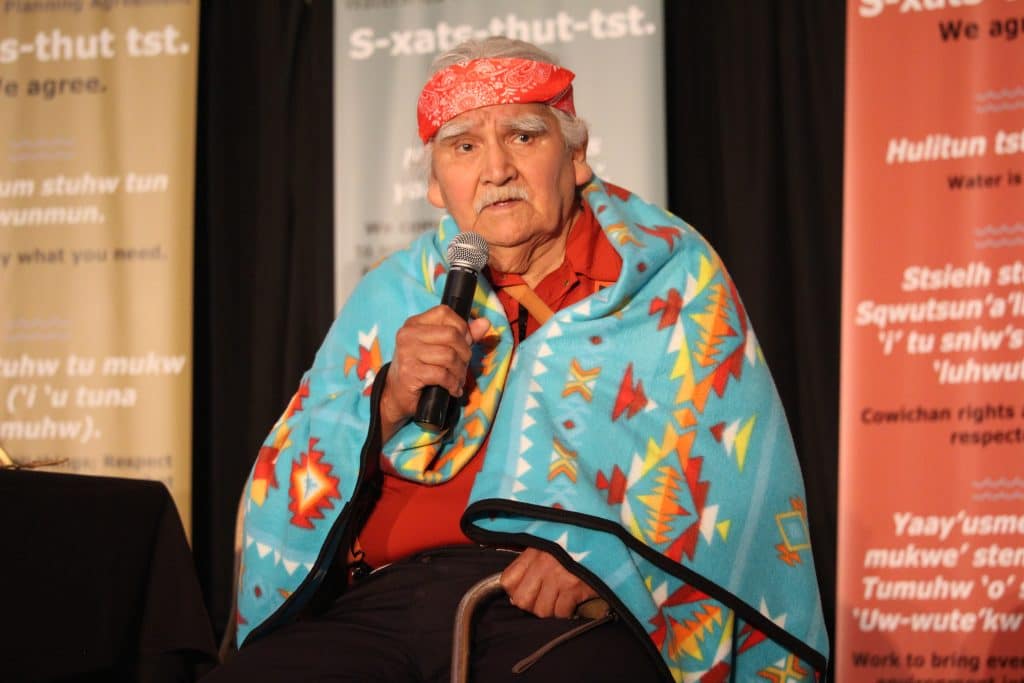

At the Xwulqw’selu Watershed Planning Agreement signing ceremony, Quw’utsun Elder Luschiim said he grew up learning about the Xwulqw’selu Sta’lo’ and shared a story about the Xwulqw’selu watershed. It was just the second time he has told the story in English.

“Our great grandfather was born in 1856 and according to reports died in 1956 — that’s the old people I rubbed shoulders with learning about the Xwulqw’selu and the rest of our territory,” Luschiim said.

The agriculture community in the region also relies on the watershed, with approximately 15 per cent of the water supporting local farms and vineyards. Privately managed forest lands make up nearly three quarters of the watershed, and residents recreate along the Xwulqw’selu at various parks and swimming holes throughout the year.

But the Xwulqw’selu has changed significantly over the years due to historic and ongoing land use — such as forestry activity, development and agriculture — as well as the devastating impacts of climate change.

“The watershed is experiencing many challenges, including droughts, floods, water quality, and threats to fish,” George said. “These issues are deeply affecting our communities. They are impacting Cowichan Tribes’ exercise of rights and access to important sustenance and cultural resources, and are also creating challenges for farmers, residents, and all of those who live in the watershed and rely on the watershed.”

Extreme weather events related to climate change, such as powerful rains and long-lasting drought, put strain on the watershed. Forestry activity in the watershed, as well as development and road-building, means there are less trees and plants to slow water down as it flows down the slopes to the river. There is also less vegetation in the watershed to absorb water and slowly release it back to the land during periods of drought.

Heavy rains send water rushing through the watershed, eroding the land it passes over. The river, which once meandered and flowed into the floodplain along various streams and tributaries, has been forced into a straight, rectangular shape giving the water less opportunities to interact with the land around it. Flooding in the communities around the watershed has become a common occurrence during the rainy season.

During times of drought, there isn’t enough water in the watershed to support wildlife and water levels become dangerously low. In response to this, the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development issued an order to specific water users — like farmers — to cease using water from the river for industrial purposes in August 2019. This was the first time an order was issued under the Water Sustainability Act to protect fish populations in the province.

The same order to cease industrial water use from the Xwulqw’selu Sta’lo’ was issued again in 2021 as extreme drought took hold of B.C. and the Cowichan Valley region.

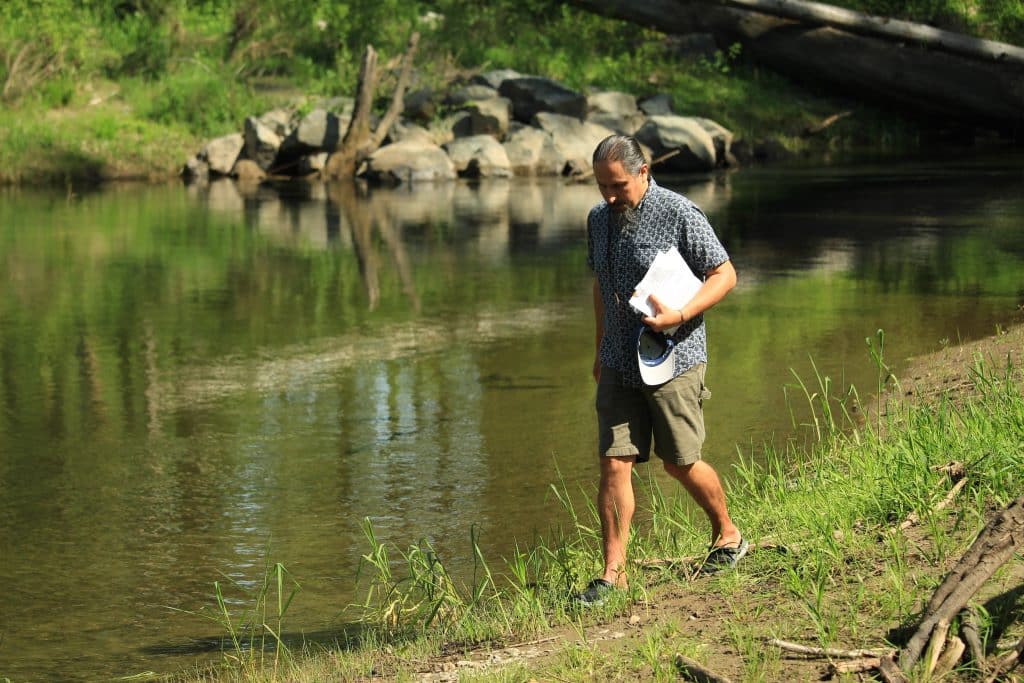

“Part of this work is that there’s a sense of urgency that we need to come together to do this work because our river is suffering,” said Hwitsum, as she stood in front of the Xwulqw’selu Sta’lo’ prior to the signing ceremony. “We’ve seen extraordinary measures in the last couple of years to ensure there are sufficient flows … Now we’re making a commitment to make a plan so that we can, in the years to come and generations to come, see the improvements in the life of our Xwulqw’selu Sta’lo’.”

Read also: New research points to solutions for Koksilah and Chemainus watershed health

Collaboration is key

Prior to the signing ceremony, Minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship Nathan Cullen, Cowichan Tribes Chief Lydia Hwitsum and team members who have worked on the water sustainability plan gathered at the lower reaches of the Xwulqw’selu Sta’lo’. Hwitsum and Cullen released salmon into the river. Hwitsum said they were returning relations into the water.

Hwtisum emphasized the collaborative effort that is necessary to support the river and watershed. From governments to private landowners in the water and community members, she said everyone will need to pitch in.

“Part of the commitment of Cowichan Tribes to ensure we save our river is such that we need to have a collaborative engagement with all of those who have an interest in the river’s health and understand that collectively, we need to make decisions that help the river,” Hwitsum said.

Cullen said he was humbled by the partnership between the province and Cowichan Tribes. He acknowledged the historic harms caused by settlers and the government to the land, water and Indigenous people who have been living on the lands for millennia. Cullen also recognized the knowledge held by Quw’utsun Mustimuhw that can help bring the river and watershed back to good health.

“We know that we have to enter this conversation with a great sense of humility as the Province of B.C. [because] we don’t have the answers,” Cullen said. “We’ve damaged many of our watersheds. We have contributed to their degradation and now we have to contribute to their restoration.”

And the work to support the river will begin right away, Cullen said. It will involve collaboration and communication across ministries and governments — such as agriculture, forestry and municipalities — and will break down historic silos that have previously kept work in each department separate.

The work will takee a whole-watershed approach, Cullen said. This means looking at the health of the river as well as the trees and land around it, including in the upper reaches of the watershed, where significant forestry activity takes place.

At the signing ceremony, Quw’utsun Knowledge Holder and biologist Q’utxulenuhw (Tim Kulchyski), said a co-governance agreement between the Province of B.C. and Cowichan Tribes is a “big step” forward for the Xwulqw’selu Sta’lo’. He noted that the river has been struggling for many years and that teams from the province and Cowichan Tribes have been working together for years to put together this first-of-its-kind formal agreement. He also noted that work to protect and steward the watersheds has been ongoing in the Cowichan Valley for years.

“In many ways, this is acknowledgement of what we’ve been doing here in the valley — what the Quw’utsun Mustimuhw have been working towards for generations but we’re coming towards a stepping stone,” Q’utxulenuhw said. “This agreement is acknowledging that stone and with this agreement we’re building a governance model here that, by principle, will look after the Xwulqw’selu Sta’lo’.”

Read also: Five ways the community can support Cowichan watersheds

What can a water sustainability plan do?

Water sustainability plans are a new legal tool, established through B.C.’s 2016 Water Sustainability Act. The Xwulqw’selu plan will be the first in the province, which opens the door for a radical reimagination of land and water management.

“Water Sustainability Plans are a powerful new legal tool with a lot of potential and flexibility to address local needs and priorities across the province,” said Deborah Curran, the executive director of the Environmental Law Centre at the University of Victoria, in a news release.

Curran co-authored a report that describes the potential for water sustainability plans to respond to water and land management issues. These plans open up new possibilities for resource management, including by allowing for new governance structures that involve First Nations and other local groups.

The plans also have the potential to link land and water management, according to the report. Regulations could establish new parameters for decision making on forestry, agriculture and urban development, based on the impacts of those activities on water. The plans can amend existing water allocations and create specific interventions for periods of critical drought.

Watershed management plans are also intended to be flexible, which means they can change in response to new conditions or priorities over time.

The details of the Xwulqw’selu Water Sustainability Plan are yet unknown, but the possibilities are wide. As the first plan of its kind in the province, it has the potential to carve a new path for others to follow.

“What happens here in the small watershed could be really precedent-setting and have impacts far beyond the Koksilah,” said Natasha Overduin, the facilitator of the planning process, at athe recent information session.

The challenges in the Xwulqw’selu watershed are rooted in the same systemic issues facing watersheds across the province and beyond, she said. “We have the opportunity to figure out changes to influence those bigger institutions, those laws, with policies, and really the culture around that.”

Read also: Reporter’s Notebook: Learnings from the Xwulqw’selu Sta’lo’

It takes a village

The initial planning process is expected to take three years, Overduin said. It will involve gathering a lot of information and consulting with all the people, organizations and industries with a stake in the watershed’s future.

One of the first steps will be to figure out the possible options, she said. What could be part of the plan? What are the priorities? Which interventions are achievable, and will have the most impact? Where will laws and regulations need to change?

“Cowichan Tribes and the province are really committed to an open and inclusive process,” Overduin said. “The idea is: no surprises, no mysteries. Everyone is aware of what’s happening.”

The partners will convene advisory tables, one for Cowichan Tribes members and another for a diverse group of people from the broader community. And there will also be working groups dedicated to bringing together experts on specific topic areas, such as agriculture or cultural ecological restoration. And, the public at large will be included as much as possible, through regular communications and invitations to offer input.

The process is designed to be circular and iterative, Overduin said. The key idea is to gather that input in a way that lands on solutions that work, and that people believe in.

“We’re here working with people that live in a system, that rely on the system, that I think for the most part want to participate and see how we can make this better,” said George. “Just from watching the system for somebody’s 50 or 70 years of observation, I think the outcome is going to be at least a very good opportunity to help Mother Nature. We’ve got to go through it and see what happens. We have to see the results and we need to participate and support and encourage and believe, and not sit back and say, ‘it’s not gonna work, it’s never gonna happen.’”