Every Tuesday for the past three years, rain or shine, a group of protestors with brightly coloured signs has lined the concrete barriers near the entrance to Goldstream Provincial Park.

On a recent Tuesday in October, passing cars and trucks honked in support of the protestors as two busloads of school children filed into the park to walk the riverside trail. Even on a cold, wet day, the parking lot was packed.

These protestors are there to raise awareness about a provincial highway project they say could threaten the Goldstream River and the wildlife that depends on it.

W̱SÁNEĆ Elder ZȺWIZUT (Carl Olsen) from Tsartlip First Nation was the first to start protesting the Malahat Safety Improvement project, which the province says aims to make the road safer and more reliable.

The work would widen a section of the highway that runs through the park, add a median barrier and improve access for cyclists and pedestrians.

According to an environmental assessment conducted for the province, the four-year project would also remove forested and riparian areas near the Goldstream River and potentially destroy Red- and Blue-listed ecosystems. In B.C., species and ecological communities that are Red-listed are considered extirpated, endangered or threatened. Those that are Blue-listed are of special concern (formerly labelled as vulnerable).

ZȺWIZUT said the proposed safety improvements for drivers would come at the cost of the habitat that salmon rely on.

“They talk about being able to minimize the damage, but I don’t know how you can say that, looking at the scope of the work,” he said.

Critics disagree with the province’s plan to increase safety at the cost of riparian habitat. They also say the plan infringes on the treaty rights of the W̱SÁNEĆ People, whose nations include Tsartlip, Pauquachin, Tsawout, Tseycum and Malahat.

In a statement to The Discourse, the Ministry of Transportation and Transit said it has been engaging with local First Nations on the project since 2019 and with the W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council — which represents the Tsartlip and Tseycum Nations — since 2022.

“Yes, they’ve talked to us, and it’s ongoing, but I sat in their their discussion groups and they’re not telling the full story,” ZȺWIZUT said.

Under the Douglas Treaties, the W̱SÁNEĆ People have the right to hunt and fish as they formerly did and Goldstream River is one place where the nations harvest chum, chinook and coho salmon.

“[Goldstream] was supposed to be protected by the government so that we could do our hunting and fishing. To have the loss of the salmon here would be devastating for the W̱SÁNEĆ People,” ZȺWIZUT said.

Impact on the ecosystem

In 2024, an environmental assessment for the Ministry of Transportation and Infrastructure was completed by consulting firm McElhanney Ltd.

The 139-page report outlines how the project will impact plants and animals that live in the surrounding forest and river.

Chief among ZȺWIZUT’s concerns is the well-being of chinook, chum and coho salmon, which use the river as spawning grounds and as habitat during their juvenile life stages.

“It’s the salmon run that we depend on for our W̱SÁNEĆ communities, just like the Quw’utsun depend on the Cowichan river for their winter smoked salmon,” ZȺWIZUT said.

The report states that one residual impact would be the “permanent loss of mature coniferous forest habitat” and “permanent loss or alteration of aquatic salmonid and amphibian habitat in proximity to the Goldstream River.”

Even just the loss of trees around the stream could have serious consequences for young salmon, ZȺWIZUT said. Juvenile salmon live in the river as they mature, and the temperature difference between shaded water and water exposed to direct sunlight could be as much as 10 C.

“There’s no time of the year that they would be able to work without damaging the fry,” he said.

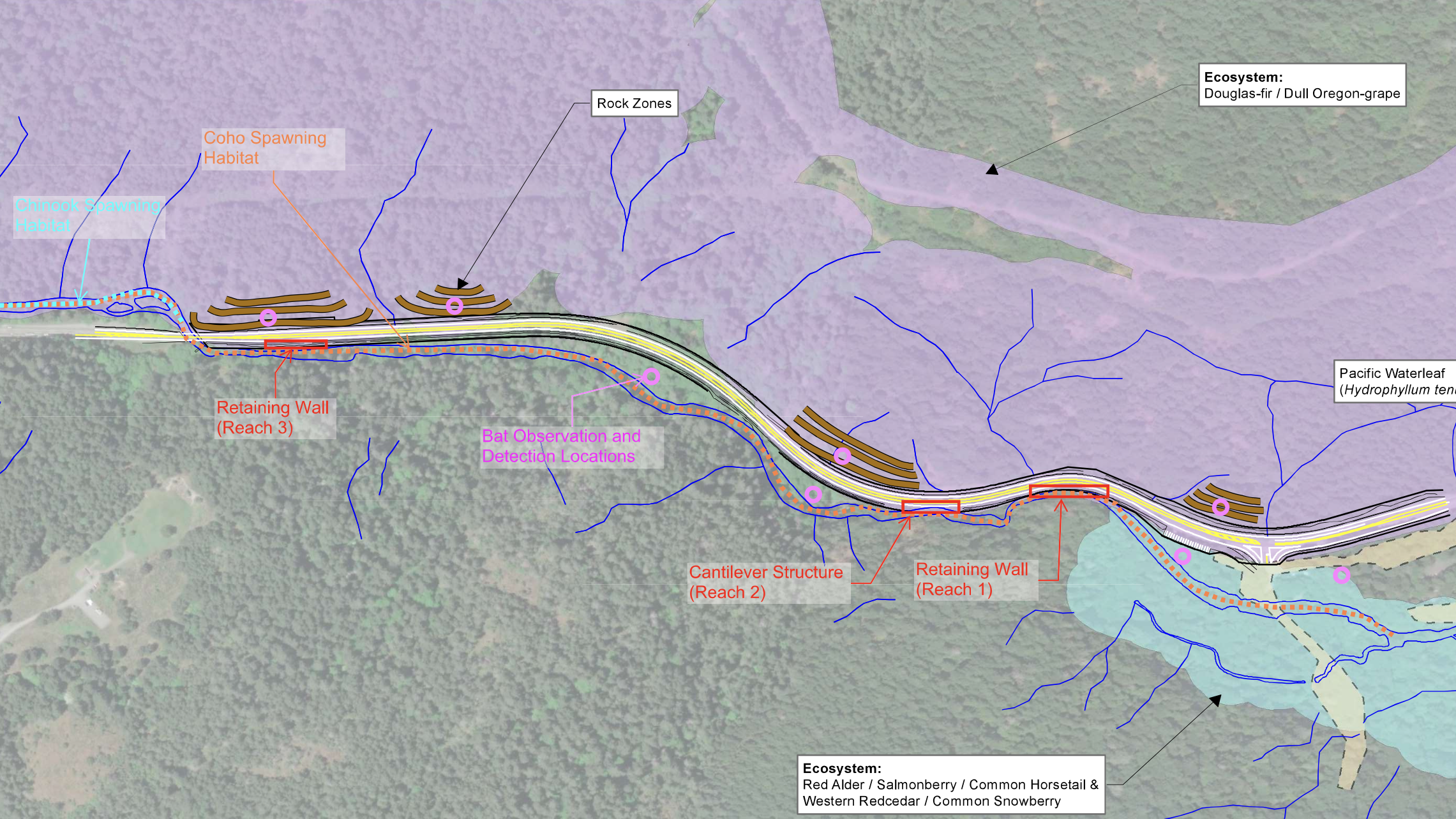

The spawning habitat for chinook and coho spans the entire length of the river, downstream from a decommissioned dam near the Goldstream Hatchery to the river delta at Finlayson Arm. The planned worksites — which include two retaining walls and a cantilever structure — fall within this stretch of the river and are located close to the riverbank.

That close proximity to spawning habitats is what worries ZȺWIZUT.

“They’re probably going to be right in the stream and disturbing it with excavators and blasting,” he said. “It’s not going to survive.”

The environmental assessment states that some work on the cantilever structure (which extends out over the stream) and retaining walls will need to take place below the high-water mark — or “instream” — and require the creation of temporary cofferdams to divert the flow of water in the Goldstream River.

The same structure will also see installation of interlocking piles and excavation next to the river, both of which require the use of industrial equipment and machinery.

According to the report, direct impacts on fish and their eggs — including disturbance, injury or mortality — could result from placement of structures in the water and use of industrial equipment.

Noise and vibrations from blasting activities on the other side of the road are also expected to impact fish in the river.

Beyond salmon, many other species at risk will be affected by the work according to Tobyn Neame, a campaigner with the Wilderness Committee.

Wilderness Committee has been helping the protestors organize a letter writing campaign to the Minister of Transportation and hold larger rallies, like the one at the legislature on Oct. 22.

The environmental assessment report identifies 18 wildlife species observed in the project area which includes other fish, bats, insects, reptiles, birds and amphibians — many of which are listed either provincially or federally as endangered.

According to the project’s website, part of the project will be focused on “environmental restoration,” riparian planting and an oil spill collection system. Neame said these are all things that need to be done, but not at the cost of existing habitat.

Upstream from the project area, the environmental assessment outlines proposed habitat restoration in sections of the river where the Department of Fisheries and Oceans previously carried out enhancement work. The work would include placing large pieces of woody debris into the river to create habitat for fish and insects and mimic a natural riparian area, as well as importing gravel ideal for coho spawning.

“The way that they’re dealing with that in the environmental assessment is to say ‘we’ll save fish and habitat elsewhere,’ but it’s still going to destroy the habitat that is there currently,” Neame said.

Will the project actually improve safety?

In a statement to The Discourse, the Ministry of Transportation and Transit said permanent safety upgrades are needed to reduce serious crashes and highway closures while also limiting the highway’s environmental impact on Goldstream River.

ZȺWIZUT and the protestors agree that the road could be made safer, but they disagree with how the province is going about it.

The project includes widening 1.7-kilometres of highway (though it will remain one lane in each direction), installing a median barrier, improving active transportation along the road and adding stormwater and highway runoff collection and treatment systems to help prevent contaminated water from entering the river.

Read more: Toxic tire chemicals are killing salmon. What can be done about it?

“There are absolutely concerns about the safety of the highway,” Neame said. “But the proposed project is going to have so many deleterious effects without necessarily increasing the safety.”

The Ministry of Transportation and Transit told The Discourse between 2020 and 2024, there were 38 crashes on this segment of the highway with 21 crashes in the past two years alone, including what they call “several serious incidents.”

“Installing a median barrier and improving the road are expected to significantly reduce the risk of head-on collisions,” the ministry said.

A 2012 review of the Malahat Highway outlined the high collision rate of the segment of the highway that runs through Goldstream, attributing many of the crashes to the Finlayson Arm intersection.

The report concludes that the stretch of the highway running through the park is the most challenging on the corridor to make improvements due to the presence of a “high rock bluff and the proximity of an environmentally sensitive creek providing spawning habitat for salmon.”

Neame and ZȺWIZUT both noted that even though the province plans to widen the highway’s footprint, it will remain a two-lane road — meaning the changes won’t reduce the amount of traffic flowing through the narrow stretch of highway.

A 2024 report by the Victoria Transport Policy Institute argued that improving bus service along the Malahat corridor could remove 10 to 30 per cent of vehicle trips, reducing traffic congestion, collisions and pollution without altering the roadway.

The province has earmarked $162 million in its 2025 budget for the improvement project, but Neame said that money would be better spent on increasing transit service along the Malahat.

“Having frequent and accessible bus service decreases congestion, but it also increases safety, because it’s fewer individual drivers,” Neame said.

A loss for future generations

“The impact will be heavy on the community, but it’s even heavier for these young people,” ZȺWIZUT said motioning to the two school buses parked nearby waiting to pick up students who were at Goldstream Provincial Park for a field trip.

He said the park offers an ideal hands-on learning experience.

“This is the best place for them to learn,” he said, explaining that classes visit to watch salmon make their way upstream and understand their lifecycle and why they return each year.

Students raise salmon from eggs in their classrooms, he added, “and before they leave school, they bring the fry back here to release them into the stream.”

The Wilderness Committee has a letter-writing tool that allows concerned people to write to the Minister of Transportation and other MLAs.

Neame said the response they’ve received from the public has been deeply personal and consistent.

“Overwhelmingly, people tell us they care about this place,” they said.

Many have been visiting the park for decades, often bringing their children to learn about nature. For them, it’s not just educational, Neame added — “it’s a place that connects us to the natural world,” and people don’t want to see it lost.

Ultimately, the Wilderness Committee would like to see funding for the project removed from the budget and the money potentially allocated to an alternate solution.

For now, the protestors will continue to stand on the highway’s edge every Tuesday until they see the changes they want from the province.

Olsen recalled one letter he received from a student which he read at the rally in Victoria.

“You kill this stream, you kill the salmon. You kill the salmon, you kill the orca,” the letter read.