Shortly after midnight on Dec. 10, the Municipality of North Cowichan council voted for the second time to deny the Vancouver Island Motorsport Circuit’s plans to rezone its property to make way for a major expansion of its track. It did so after nearly six hours of public input that was overwhelmingly against the expansion. Council also did so in the face of a lawsuit threat from VIMC, which the company’s lawyers say could exceed $60 million in damages. (The letter threatening the lawsuit is included in council’s Dec. 9 agenda package on page 57.)

VIMC is threatening to sue on the basis that it believes that the municipality is legally required to grant a permit for the expansion. And, that if the municipality does not, it puts the entire business in jeopardy. Last week North Cowichan CAO Ted Swabey presented a report on the potential tax implications if VIMC successfully sues for damages. Based on that report, the Cowichan Valley Citizen published the headline: “North Cowichan taxpayers could face a one-time 133% increase in ‘worst case’ VIMC lawsuit.”

But how realistic is that worst-case scenario? Should North Cowichan taxpayers be worried?

I reviewed public documents and legal precedents, and I researched to find answers. I also spoke with Deborah Curran, an associate professor who teaches municipal law at the University of Victoria. She helped walk me through the areas of municipal law that apply to this case. She told me about how these sorts of cases generally go, but did not comment on the specifics of the potential legal action between VIMC and North Cowichan.

“Generally, municipalities have virtually complete control on private land as to say what happens and what does not happen on private land,” Curran tells me. “It is important to note that we are working in a Canadian context, where land use regulations are the norm. Extensive land use regulation is the norm — that is a term that’s used in the court.” Of course there are limits to these powers, and it is at the boundary of these limits that VIMC presumably hopes to make its case.

Council moves to neuter legal threat

VIMC’s threat letter claims that, if the municipality doesn’t allow the track to expand on neighbouring industrial land on the basis that it is not a permitted use, it is de facto saying the existing track, also on industrial land, is operating illegally. This, the letter argues, would force the closure of the facility and put North Cowichan on the hook for nearly $40 million spent on Phase 1 plus damages associated with the planned expansion and interrelated businesses. That’s how the lawyer explains he arrived at, by “rough calculations,” more than $60 million in damages.

Council made a big move on Tuesday night, apparently in an attempt to eliminate most of the damages VIMC says it could be owed. The council began the process to rezone the land where VIMC currently operates so that a “Motor Vehicle Testing and Driver Training Facility” is explicitly allowed there.

If council passes the rezoning, which is expected to come before council again in January, it could reduce the likelihood of VIMC successfully suing for damages that relate to the money already spent on the existing facility. That’s because the rezoning would provide assurance that Phase 1 is operating legally. In this scenario, VIMC is potentially more likely to sue to recoup money spent on the planned expansion, but those are unlikely to exceed the municipality’s $20 million in liability insurance.

VIMC could attempt to sue to force the expansion

However, that doesn’t mean the lawsuit threat is eliminated. If VIMC is unhappy with the denial of its expansion plans, there are a couple of ways the company could go about suing North Cowichan. One would be to ask a judge to review the municipality’s decision to deny VIMC a development permit to go ahead with the expansion. In theory, a judge could order North Cowichan to allow the VIMC expansion. And, in another letter, VIMC’s legal team cites cases where judges did just that. (The letter is on page 62 of the agenda package.)

But developers have to meet a high bar to succeed in these cases, Curran tells me. “It would be very rare that a court would require the local government to issue the development permit.” More typically, if a judge finds the council denied the permit based on improper considerations, they would then ask council to make the decision again, taking into account the appropriate considerations, she says.

To force the expansion, the court would potentially have to find that the track is a permitted use on heavy industrial-zoned land, and therefore must be permitted to proceed. However, that goes against North Cowichan staff’s current interpretation of the bylaw, recently confirmed by North Cowichan’s director of planning, Rob Conway (his letter to VIMC confirming this is on page 54). And, as previously mentioned, municipalities hold a great deal of power when it comes to setting their own land use rules.

“Unless [a use] is permitted in a zoning, it’s prohibited,” Curran says. “This is unlike many areas of law, where you’re permitted to do something unless you’re prohibited. In zoning it’s the exact opposite.” Where there’s disagreement on the interpretation, it’s up for a judge to decide.

VIMC could attempt to sue for damages

Alternatively, VIMC could abandon its expansion plans and sue the municipality for its losses related to the planned expansion. One recent letter suggests VIMC plans to go this route. However, it’s impossible to say what the company will do, if anything. Sean Hern, author of that letter and a lawyer representing VIMC, declined to comment when I reached him by phone on Dec. 10.

If successful, the municipality could be on the hook for some concrete costs related to the expansion. For example, some of the costs of purchasing the adjacent land and the costs of planning the expansion.

Developers rarely succeed in recouping these costs, Curran tells me. “In very rare circumstances court will find the public authority to be liable,” she says. “That has to be qualified quite significantly. It’s very rare.”

To successfully sue for damages, VIMC would have to show that it had assurances from the municipality that the track expansion would be permitted. And it would have to show that it was reasonable to rely on those assurances in proceeding with its plans.

VIMC points to written assurances from North Cowichan staff, from 2013 and 2015, that the initial Phase 1 track would be permitted to operate on the industrial lands. (Those letters are available on pages 64-65 of the agenda package.) It says, based on that, it expected a development permit would be issued for an expansion of the track on adjacent lands with the same zoning.

Curran says that, in general, it may not be wise to apply assurances regarding one property to another. “Each property is so different, and different discretionary factors go into each property. In my view, you cannot rely on a statement about one property, even if it’s the same zoning, and then apply it to another property.”

What happens to the properties?

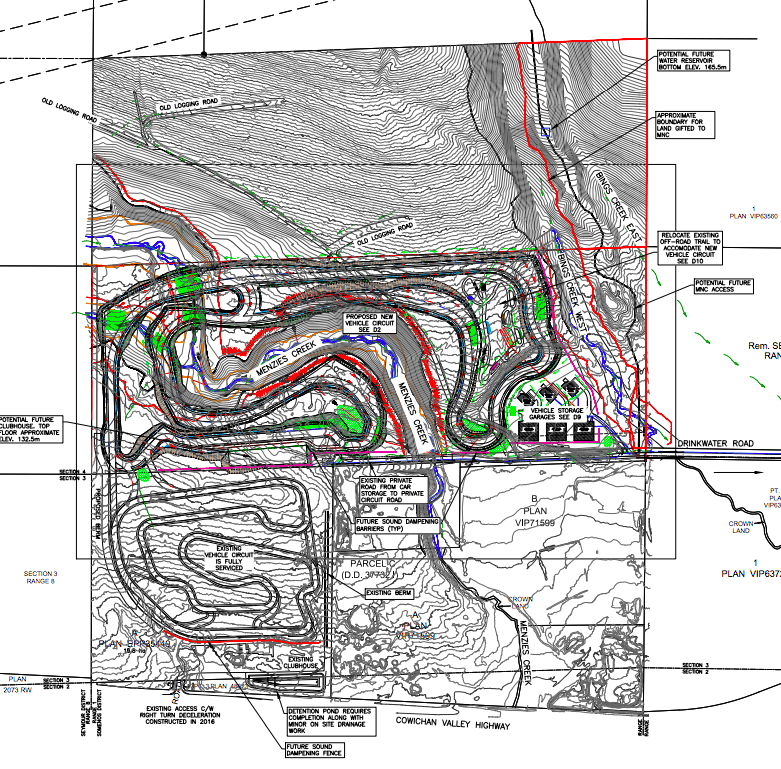

VIMC owns two parcels of land to the north of its existing facility. The nearest is zoned for heavy industrial use, and the other is a rural resource zone. The rural resource property was initially part of the track expansion plans, and later revised out of it. At the first public hearing, VIMC agreed to sell that parcel to North Cowichan at market price. After the hearing, VIMC agreed to gift it to North Cowichan with the intention that it be given to Cowichan Tribes, Mayor Siebring said at the Dec. 9 hearing.

Now, with council’s denial of the rezoning, those promises have disappeared, as CAO Swabey confirmed at the meeting early Tuesday morning. VIMC has not, based on documents that have been made public to date, claimed that it was assured anything related to the rural resource lands. The company could conceivably do any number of things with that land. Those might include doing nothing, selling it, developing it for a use that is already permitted, or applying to rezone it for a different use. Permitted uses on that land, zoned A4, include forestry use, manufactured homes, mobile food service, resource use, single-family dwellings, temporary mobile homes, wilderness recreation and wildlife refuge. (These are described in North Cowichan’s Zoning Bylaw, page 43.)

As for the industrial lands closer to the existing track, it’s possible VIMC will seek a judge’s intervention to either allow the track expansion or seek damages. Alternatively, or perhaps additionally, VIMC could sell, develop or apply to rezone that land. Current permitted uses on that land include auto wrecking yards, cannabis production facilities, helicopter landing pads, private airplane landing strip, industrial recycling, sawmills, slaughterhouses and more. (The full list is in North Cowichan’s Zoning Bylaw, page 88.)

What’s next?

Now, it’s a waiting game to see how VIMC responds to council’s latest move. That move could be the announcement of a lawsuit, or land for sale. Or something else. The saga, in all likelihood, is far from over. [end]

Corrections: A previous version of this article incorrectly called North Cowichan’s A4 land use zone a “type of agricultural” zone. It is in fact a rural resource zone. A previous version of this article incorrectly attributed North Cowichan’s letter confirming that the track expansion is not a permitted use on heavy industrial land to CAO Ted Swabey. It was in fact written by planning director Rob Conway. (December 12, 2019)