- The Municipality of North Cowichan owns 5,000 hectares of forest land. That’s about 12 Stanley Parks. Every year, the municipality cuts down some of the trees and sells the logs, which helps to fund municipal services and programs.

- The municipality is currently reviewing how it manages the forests. People can tell the municipality what’s most important to them about the forests in a survey until Dec. 13, 2021. There is a discussion guide with more information.

- These forests are very important to the Quw’utsun people. The Quw’utsun Nation has agreed to ongoing talks with North Cowichan about the management of these lands.

- These forests are very important ecologically. They are part of the rarest and most endangered ecosystem in British Columbia, where many endangered species live. A lot of the forest is healthy, which is rare for forests of this type.

- The next articles in this series will dive deeper into possible alternatives for managing North Cowichan municipal forests. Subscribe to The Discourse Cowichan to stay in the loop.

On Nov. 22, North Cowichan began a public consultation on the future of its municipal forest lands, located on unceded Quw’utsun Nation territory. The community has a rare opportunity to set the vision for the future of this significant piece of forest land, as big as 12 Stanley Parks.

The lands in question include much of Mount Prevost, Mount Tzouhalem, Mount Sicker, Maple Mountain, Mount Richards and Stoney Hill. These areas are important to many people for many reasons, including for recreational opportunities, cultural activities, rare ecological features and more. In an ecosystem where little old growth remains, North Cowichan’s municipal forests hold significant potential to become the old growth of the future.

The municipality has logged and replanted about 30 per cent of the area since 1987. Profits from selling the trees support municipal services and programs. Now, the municipality is consulting First Nations, the public and experts on how the forests can best be managed into the future.

The process is both well behind schedule and right on time. After a devastating year of deadly heat waves, wildfires, old-growth blockades, floods and drought, the conversation about the future of the forests has never been more urgent.

A unique set of circumstances align in North Cowichan. It’s a chance to lead the way on how you bring a community together for a difficult conversation towards a shared goal: healthy forests that support healthy communities.

“It’s an opportunity. Incredible opportunity,” says Barry Gates, a local forest land manager and co-chair of the Ecoforestry Institute Society. The society owns and manages the Wildwood Ecoforest, located fewer than 30 kilometres from North Cowichan’s northern boundary. “North Cowichan has a beautiful little site, small enough you can do really effective planning and big enough to make a difference.”

What’s so special about North Cowichan’s forests?

A few things make the municipal forest unique and special for several reasons. The first is just the fact of it. Few municipalities own and manage significant forest lands. Louisville, Kentucky’s Jefferson Memorial Forest claims to be the largest city-owned forest in the United States, and it’s half the size of the North Cowichan municipal forest reserve.

In B.C., community forests are more typically located on Crown lands and managed through lease agreements with the province. (The Cumberland Community Forest Society is an exception. The group has purchased its forest outright through community organizing and fundraising. It owns about 200 hectares, compared with 5,000 owned by North Cowichan.)

The North Cowichan forests are a highly valued community asset. An extensive trail network covers much of the land, where hikers and bikers go to play, and volunteer groups work hard to maintain and improve it. Mount Prevost has been called “the lifeblood” of Canada’s downhill mountain biking scene. And Mount Tzouhalem’s parking lot became so overwhelmed during the pandemic that it was causing significant conflict with neighbours, prompting North Cowichan to develop new access points to the mountain.

The lands are also really important to the Quw’utsun people, who have used them for food, shelter, medicine and ceremony since time immemorial. The Quw’utsun Nation is a reclaimed political organization that includes Cowichan Tribes, Halalt First Nation, Lyackson First Nation, Penelakut Tribe and Stz’uminus First Nation. The Quw’utsun Nation is in ongoing discussions with North Cowichan about the municipal forest lands.

And the forests are also ecologically rare and important. Much of the land is part of the rarest and most endangered ecosystem in B.C. The forests are reasonably old and healthy, which makes them particularly important and valuable.

To cut, or not to cut? The question — is so much more complicated than that.

Business-as-usual is, of course, an option. Or, the municipality could stop all commercial harvesting. That option could bring in just as much money as logging, a report commissioned by North Cowichan suggests, if the municipality sold carbon credits instead.

But then there are a million middle ways. What’s important to protect? How should the forest be best put to use, and how, and where? It’s up to the community, together, to come closer to the answers.

This article is the first in a series. It will get into a bit of the history and why these lands are particularly special. The next articles will imagine possible futures for the forest, drawing on lessons from elsewhere. There are resources for further learning at the bottom of this article.

A short history

A quirk of history put North Cowichan in this unique position. The story goes back to the E&N Land Grant of the 1880s. The colonial government of the day gave away an enormous tract of land on Vancouver Island to the E&N Railway Company in exchange for a promise to build a railway. The grant spanned the east side of the Island between what’s now Langford and Campbell River.

The Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group calls this deal “a clear act of colonial theft,” and continues to dispute its validity. The group represents Cowichan Tribes, Halalt, Lyackson, Ts’uubaa-asatx and Penelakut at the provincial treaty negotiation table.

The railway company later sold off the land in pieces, mostly to forestry companies. (Still today, 60 per cent of Hul’qumi’num territory is owned by just three forestry companies.) Much was ultimately sold off for urban development and agriculture, too. The result is the patchwork of private ownership up the coast of the Island today.

North Cowichan’s municipal forests were previously owned by forestry companies, too. But after logging what they could, the companies stopped paying their municipal tax bills. Over the 1930s and 1940s, North Cowichan appropriated the lands in lieu of the taxes owed.

Council designated the lands, a size of about 5,000 hectares, as a forest reserve in 1946. It covers a quarter of the land in North Cowichan’s borders.

In late 2018, a group of citizens, organized as Where Do We Stand, asked for a pause on logging in the forest reserve to allow for consultation with experts and the public, “in light of accelerating ecological, economic, and social changes.” Hundreds of people showed up at a council meeting, filling council chambers and an overflow room, too, to demand a say on forestry in North Cowichan.

Under intense public pressure, the municipality agreed to review its forest management. It hired a group of forestry experts at UBC for a technical review and planned public consultations.

The municipality also reached out to First Nations, and paused the public consultation to give space for those discussions.

In August 2021, North Cowichan and the Quw’utsun Nation reached an agreement to form a working group, which will meet regularly to discuss concerns related to the municipal forests. Additionally, at least four times a year, elected representatives for the First Nations and the municipality will meet for government-to-government consultations.

The forest management review, initially scheduled to be almost complete by now, is only getting started.

Unceded land

Long before the municipality of North Cowichan existed, before the E&N Land Grant, before Europeans stepped foot on Cowichan shores, the Quw’utsun people were the owners and stewards of the lands and forests.

These lands are the heart of Quw’utsun territory. The Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group’s 2005 land use plan shows significant overlap between the municipal forest and lands that were used intensely for harvesting and cultural uses, while also being significant places in oral tradition. That’s true especially for Shquw’utsun (Mount Tzouhalem and Stoney Hill) and Swuq’us (Mount Prevost and Mount Sicker).

These lands hold many stories, many of which are not shared publicly. Swuq’us is central to the Quw’utsun creation story. It is where one of the original people fell down to Earth from the sky.

Related article: The ancient story of Swuq’us

Tzouhalem holds the story of the legendary Chief Ts’uwxilum, who is both a historical and mythical figure.

Related article: Who was Chief Tzouhalem?

Salish Peoples were forest managers. Among other things, they set fires to clear the understory and maintained Garry Oak meadows, rich with camas. The camas bulb was a significant food source for Quw’utsun families.

Now, without widespread Indigenous management, those landscapes are endangered, and the wildfire risk is increased.

The history of privatization of Quw’utsun territories also presents a challenge for the treaty process. The B.C. government holds that private lands are off the table in terms of treaty negotiations. But what does that mean for the Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group, whose territories have been widely privatized?

“We’re still in that conundrum. How is this going to get resolved?” asks Robert Morales, chief negotiator for the Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group, in a recent interview with The Discourse. “There has been no positive court decision that has dealt with this outstanding question. And the outstanding question is, what are the land rights of First Nations whose traditional territories have been unlawfully confiscated?”

The rarest ecosystem in B.C.

North Cowichan’s municipal forests are special, too, because they hold some of the rarest and most endangered species and ecosystems in the province.

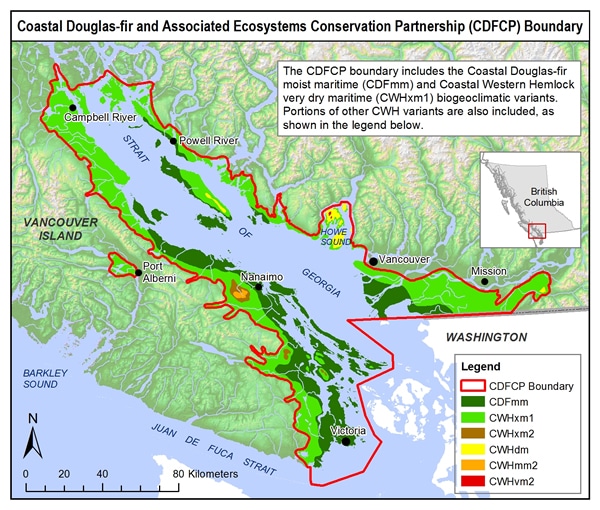

The province of B.C. is composed of fourteen different “biogeoclimatic zones,” meaning areas that share similar weather patterns and ecosystems. Of those, Coastal Douglas-fir (CDF) is the rarest and the most endangered. A significant portion of the North Cowichan municipal forest is within the CDF zone, and most of the rest is in the closely related “very dry” variant of the Coastal Western Hemlock zone.

CDF exists only in a slim band of Vancouver Island’s east coast, the Gulf Islands and the fringe of the southern mainland coast. This ecosystem is unique in part due to the rain shadow effect, which creates a mediterranean-like climate close to sea level.

CDF ecosystems overlap with the parts of this province that have been the most privatized, the most urbanized and the most heavily logged. While 94 per cent of B.C. is so-called Crown land, 80 per cent of CDF is privately owned. Half has been permanently converted to agricultural use or urban development. Less than one per cent of CDF forests remain in old-growth condition. And these areas are home to more endangered species that other ecosystems in the province.

A 1999 report by the B.C. government called for urgent action by everyone to promote conservation and restoration of CDF ecosystems. Since then, the situation has not improved. With most of the CDF zone blasted apart into tiny private land holdings, environmental protection and restoration efforts are disjointed and ad hoc.

Here, too, North Cowichan has an opportunity for outsized impact. The municipality is likely to be among the largest owners of CDF land, says Gates, with the Ecoforestry Institute Society.

The ‘best of the last’

North Cowichan’s forests are special not only because they hold a lot of rare ecosystems, but because those ecosystems are relatively healthy and in good shape, says Peter Arcese, the Forest Renewal BC Chair in Conservation Biology at the University of British Columbia. Arcese is among the UBC experts that North Cowichan has hired to lead the technical review of how it manages its forests.

Parts of North Cowichan’s municipal forests often come up when seeking to identify areas of high potential conservation value, because they are the “best of the last,” Arcese says. “The landscape in many respects around that area is quite unique and in very good shape, and always comes onto our radar as a place that’s contributing positively to the persistence of plant and animal communities that don’t exist elsewhere in the world.”

But the UBC group’s role is not to say what should happen for the future of the forests — it’s up to the community to set the vision based on what it values. “I try not to judge too much about what exactly we should do, but I do advocate for policies that would lead to good outcomes for species and people,” Arcese says.

“In general, I’ll have to say, your foresters have been doing a good job of managing them,” says Arcese.

Gates agrees that the good condition of the North Cowichan forests is part of what makes them special.

Much of the forests are at least 80 years old, and regenerated naturally after they were last cut. That means that no trees were planted, and the forest was left to grow back on its own. That’s a good thing, ecologically speaking, Gates says. Nature does a better job of putting the right species in places suited to them, but it takes time.

“Eighty years of natural regeneration, that’s really a goldmine,” he says. “It’s moving towards old growth.”

Forests develop the characteristics of old growth over time, and recovering those old-growth features is really important in CDF forests, where true old growth is so rare, Gates says. And restoring old-growth forests doesn’t always mean leaving them alone completely. Some management activities, including harvesting select trees for lumber, can actually speed up a forest’s development of old-growth features.

Setting a precedent

When it comes to managing the forests for maximum community benefits, better is absolutely possible, Gates says.

The province is in the midst of reviewing its own management of forests on Crown lands. It has promised a new way forward, one that does a better job protecting old-growth ecosystems and other valuable environmental features, while giving First Nations and the public more of a say.

Related article: Where are the proposed old-growth deferrals for Vancouver Island?

That process does not apply to private lands, including the North Cowichan municipal forest. However, North Cowichan is attempting to accomplish something strikingly similar, on a smaller scale.

It’s a good opportunity to show what more comprehensive forest management looks like, says Gates. “Why not be a precedent setter?” [end]

This article is part of the Forests for the Future solutions series. Subscribe to The Discourse’s Cowichan Valley newsletter to stay in the loop.

Resources to learn more

- North Cowichan’s public survey runs through Dec. 13, 2021. Find it here. And here’s the accompanying discussion guide. There will be virtual workshops on Nov. 24, Nov. 27 and Dec. 2. Find registration links here.

- Find more background information on the municipal forest, compiled by North Cowichan, here.

- Here’s a link to more information on the potential to develop a carbon credit program in North Cowichan.

- Explore the municipal forests with this interactive web map. Find information about recreational access to the municipal forest here.

- The Coastal Douglas-fir Conservation Partnership’s website has more information about conservation issues in Coastal Douglas-fir and related ecosystems.